| Midway upon the journey of our life I found that I was in a dusky wood; For the right path, whence I had strayed, was lost. – opening lines, Dante’s Divine Comedy |

Interior of bowl Deer antlers swirl around the four cardinal points of the earth -earl 4th millenium B.C. Bilcze Zlote, northwestern Ukraine |

PART I: THE ANCIENT WORLD

Merlin the magician foresaw a day “when all the wisdom from the heart of the green world would be lost and buried,” an observation that acquired a keener edge when our press noted that approximately seventy per cent of food available in Canadian supermarkets is of the genetically engineered variety. Concerns that a captive populace had been pressed into service as unpaid lab rats were pooh-poohed by our Minister of Agriculture. Lyle Vanclief informed mutating masses: “The science of biotechnology is continuing to advance and Canada needs to remain on the leading edge.” Translation: Your rogue chromosomes are someone else’s department. Nature, that consummate healer, may be generally forgiving of our little lapses, but when we come to our senses late in the day, it may be altogether too late for us if we persist in sleeping through the alarm. There was a time, though, when we saw ourselves as integral components of Nature’s divine plan, not overlords.

Mouse growing a human ear “to order”

We think now of the old European worship in sacred groves as some kind of shameful family secret, on the order of keeping crazy Aunt Dottie chained in the attic for decades on end. Sneer as we may at our ancestors’ abiding covenant with nature, science has known for the last century that deeply embedded within vascular bundles, neural strands run through plant anatomies, effectively linking roots, stems, branches, leaves and flowers. These neural strands discharge negative electrical impulses when the plant is in any way disturbed or stimulated. We can only suppose that plants are some manner of sentient beings: they certainly respond to music, react to pain, to pleasure, and, on some mysterious level, communicate those experiences. In any event, we don’t understand whales and dolphins either, but perhaps marine mammalian intelligence is simply better suited to commercial exploitation.

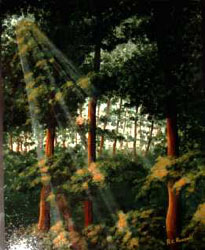

Getting beyond Genesis and the Tree of Knowledge isn’t always easy; somehow, whenever we try to examine this European tree kinship thing, we resort to the diabolical phantasm outlined by the 1st century AD poet, Lucan. He described a sacred grove near Marseilles in these terms: “Interlacing boughs enclosed a space of darkness and cold shade, and banished the sunlight from above. … Gods were worshipped there with savage rites, the altars were heaped with hideous offerings, and every tree was sprinkled with human gore. On these boughs … birds feared to perch; in those coverts wild beasts would not lie down. … Legend also told that often the subterranean hollows quaked and bellowed, that yew-trees fell down and rose up again, that the glare of conflagration came from trees that were not on fire, and that serpents twined and glided round the stems. The people never resorted thither to worship at close quarters, but left the place to the gods. When the sun is in mid-heaven or dark night fills the sky, the priest himself dreads their approach and fears to surprise the lord of the grove (dominum luci).” [1]

Getting beyond Genesis and the Tree of Knowledge isn’t always easy; somehow, whenever we try to examine this European tree kinship thing, we resort to the diabolical phantasm outlined by the 1st century AD poet, Lucan. He described a sacred grove near Marseilles in these terms: “Interlacing boughs enclosed a space of darkness and cold shade, and banished the sunlight from above. … Gods were worshipped there with savage rites, the altars were heaped with hideous offerings, and every tree was sprinkled with human gore. On these boughs … birds feared to perch; in those coverts wild beasts would not lie down. … Legend also told that often the subterranean hollows quaked and bellowed, that yew-trees fell down and rose up again, that the glare of conflagration came from trees that were not on fire, and that serpents twined and glided round the stems. The people never resorted thither to worship at close quarters, but left the place to the gods. When the sun is in mid-heaven or dark night fills the sky, the priest himself dreads their approach and fears to surprise the lord of the grove (dominum luci).” [1]

| Those trees in whose dim shadow The ghastly priest doth reign The priest who slew the slayer, And shall himself be slain. – Macaulay |

“Ultimate power must be mine!”

We just can’t seem to give ourselves a break, can we? We are everlastingly predisposed to believe the best of others while perpetually skinning ourselves. Existing primitive, even primate, cultures are marketed as our moral superiors, while our own tribal legacy is perforce hateful, inexcusable, untenable. Very much victims of our own success, we are left with the dissonant sense that while racial characteristics simply do not exist in others; among our own kind, some pretty persistent genetic flaws continue to inform our every action. Lucan fails to mention that he is very much the interested party; by the time of his writing, the charnel chuck he describes in such lurid detail had been long since extirpated by Caesar. Standing squarely in the way of progressive plans to fortify Marseilles, that magic grove of dodonian oaks, holly oaks and alder just had to go.

Nor does Lucan admit that Caesar had had to grab an axe and topple the first tree before Roman soldiers, not so long “out of the grove” themselves, dared join the desecration. Thus, with a demoralized Gaul firmly under the Roman sandal, Tiberius issued an edict prohibiting Druidic practices in AD 37 (two years before Lucan was born). In his Histoire de la Gaule, III, V, the great French historian, Camille Jullien, described a defeated Celtic coastal tribe in these terms: “This strong and vigorous nation of the Veneti, whose origins and power go back to the builders of the dolmens, the most ancient and original of all Gaul, ended in slavery and death.” To this day, retirement from public life is just that much more congenial when one has managed to convince nearly everyone that our little acts of transgression, annihilation and destruction have somehow made the world “a safer place”. This is imperialism’s oldest (and political correctness’ newest) excuse: “Just watch these backward heathens flourish once we impose the glories of our matchless New World Order!”

Fanciful rendering of a Druid, “Britannia Antiqua Illustrata”, 1676In 58 BC, Julius Caesar became governor and military commander of the Roman province of Gaul, which comprised modern France, Belgium, and portions of Switzerland, Holland, and Germany west of the Rhine. In 55 BC, he crossed the channel and invaded Britain with two Roman legions (about 10,000 soldiers). A year later, 800 ships delivered five legions and two cavalry troops. Nevermind that in Britain Caesar found high populations, flourishing farms, extensive grain fields, and active mining operations supplying the more than half dozen tribes producing their own coinages. Nevermind that “Druidism was regarded as an ancient institution in the times of Aristotle, the 4th century BC.” [2] Nevermind that this same writer, Diogenes Laertius, stated that the Druids taught “that the gods must be worshipped, no evil done, and virtuous behavior maintained.” Rome would deal with these northern tree worshippers much as it would later worshippers of Christ; and in the way of all uneasy population mixes, an initial lull to valuate strengths was succeeded by opprobrium and proscription.

Of Britain, Tacitus says: “The island fell, and a garrison was established to retain it in subjection. The religious groves, dedicated to superstition and barbarous rites, were levelled to the ground.” Those who imagined their conquerers might share in power were disabused of the fantasy; as Tacitus makes plain: “Prasutagus, king of the Iceni [tribe], famed for his long prosperity, had made the [Roman] emperor his heir along with his two daughters, under the impression that this token of submission would put his kingdom and his house out of the reach of wrong. But the reverse was the result, so much so that his kingdom was plundered by centurions, his house by slaves, as if they were the spoils of war. First, his wife Boudicea was scourged, and his daughters raped. All the chief men of the Iceni, as if Rome had received the whole country as a gift, were stripped of their ancestral possessions, and the king’s relatives were made slaves.” [3]

Gladiator’s proverb: “Ut quis quem vicerit occidat” (Kill the defeated, whoever he may be) – The Dying Gaul, Capitoline Museum, Rome, ca. 230 BC

| Come to me, human faces, Familiar memories; I have found hateful eyes Among the desolate places, Unfaltering, unmoistened eyes. – WB Yeats, The Celtic Twilight |

Thus, Lucan’s, as much as Tacitus’ on-the-spot observations of Druidic practices must be seen for what they are: suspect chronicles of outlawed devotions by the forces that had come to destroy them. The policy of imposed Romanization, that ancient equivalent of multicultural and diversity training, was determined enough to arouse even Tacitus’ pity: “Among the conquered it is called culture, when in fact it is part of their slavery.” Not that the Romans didn’t have good reason to fear their subject northern peoples — after all, they would eventually get around to sacking Rome. So enamoured of war were the Celts that a male child’s first terrestrial meal came, not from his mother’s breast, but from the tip of his father’s sword. Caesar remarked on these pale, fearless giants who strode naked into battle, and, for the sheer sport of it, casually ran up and down connecting bars of the chariot shafts while their horses flew at full gallop. As for the deadlier sex, Ammianus Marcelinus shuddered: “A whole troop of foreigners would not be able to withstand a single Celt if he called his wife to his assistance. The wife is even more formidable. She is usually very strong, with bright blue eyes; in rage her neck veins swell, she gnashes her teeth, and brandishes her snow-white robust arms. She begins to strike blows mingled with kicks, as if they were so many missles sent from the string of a catapault.” Highly individualistic and insular by nature, by the time the Celts finally united against their invaders, it was already too late.

Thus, Lucan’s, as much as Tacitus’ on-the-spot observations of Druidic practices must be seen for what they are: suspect chronicles of outlawed devotions by the forces that had come to destroy them. The policy of imposed Romanization, that ancient equivalent of multicultural and diversity training, was determined enough to arouse even Tacitus’ pity: “Among the conquered it is called culture, when in fact it is part of their slavery.” Not that the Romans didn’t have good reason to fear their subject northern peoples — after all, they would eventually get around to sacking Rome. So enamoured of war were the Celts that a male child’s first terrestrial meal came, not from his mother’s breast, but from the tip of his father’s sword. Caesar remarked on these pale, fearless giants who strode naked into battle, and, for the sheer sport of it, casually ran up and down connecting bars of the chariot shafts while their horses flew at full gallop. As for the deadlier sex, Ammianus Marcelinus shuddered: “A whole troop of foreigners would not be able to withstand a single Celt if he called his wife to his assistance. The wife is even more formidable. She is usually very strong, with bright blue eyes; in rage her neck veins swell, she gnashes her teeth, and brandishes her snow-white robust arms. She begins to strike blows mingled with kicks, as if they were so many missles sent from the string of a catapault.” Highly individualistic and insular by nature, by the time the Celts finally united against their invaders, it was already too late.

Celtic women wedded, divorced, inherited and led in their own right; by Joan’s day, female warriors in the tradition of Boudicca or Cartimandua were deemed to be possessed by demons

Immortals. In contrast to Lucan’s grove-of-horrors, Tacitus did grudgingly concede: “The grove is the centre of their whole religion. It is regarded as the cradle of the race and the dwelling-place of the supreme god to whom all things are subject and obedient.” Here, at least, we understand how it was that these sacred groves, the immediate precursors of the classical temples, functioned; not as a pan-European slaughter-house franchise but as sacred places of sanctuary among the various tribes of the Celts, early Greeks and Romans, Balts, Norse, Teutons and Slavs — indeed, the entire European family of peoples.

Genius begets genius – JMW Turner’s “The Golden Bough” inspired Sir JG Frazer’s 13 volume namesake masterpiece

Genius begets genius – JMW Turner’s “The Golden Bough” inspired Sir JG Frazer’s 13 volume namesake masterpiece

For all their ferocity, the Northmen were not precisely what we might now consider barbarians. Ammianus Marcelinus again: “The Gauls are all exceedingly careful of cleanliness and neatness, nor in all the country, and most especially in Aquitania, could any man or woman, however poor, be seen either dirty or ragged.” [4] Pliny mentions a cosmetic soap favoured by Celtic women, while other writers remark on the perfumes and exquisite workmanship of Celtic goods. However, sentiments like these were very much the exception; the “barbarian” stigma stuck, and north Europe’s invaders (mercifully blind to the Coliseum gore-fest peddled as entertainment back home) mostly professed outrage at primitive local behaviour. Presumably though, even the most biased chronicler made some kind of private distinction between gushing blood sport and sacrificial observance as an expression of social responsibility; of sharing what one has with others, and with the originators of all bounty — the

Classical columns evolved from the sentinel trees of the sacred grove

The old Celtic “word for a ‘sanctuary’ seems to be identical in origin and meaning to with the Latin ‘nemus’, a grove or woodland glade. … From an examination of Teutonic words for ‘temple’ Grimm [that great compiler of Germanic folk tales] has made it probable that amongst the Germans the oldest sanctuaries were natural woods. … Proofs of the prevalence of tree-worship in ancient Greece and Italy are abundant. … In the Forum, the busy centre of Roman life, the sacred fig tree of Romulus was worshipped . … The withering of its trunk was enough to spread consternation throughout the city.” [5] The image of Jupiter at the Capitol in Rome was originally an oak tree; it is understood that temples evolved merely as an afterthought: shelter for the genius loci in need of additional protection. At Upsala, the old religious capital of Sweden, there was a sacred grove in which every tree was regarded as divine. “In Baltic paganism, it is believed that there is a component of the human being, the “Siela”, that does not depart with the “Vele” (soul), but becomes reinca rnate on Earth in animals and plants, especially trees. In pagan times, no abuse of tree or animal was tolerated. … It was considered sacrilegious to hit the Earth, spit on her or otherwise abuse her.” [6] Yggdrasil, the Norse World Tree, provided a complex template for good and evil, god and man, all that was — and was to be. Perpetual fires blazed before the sacred oaks revered by the ancient Prussians. The ancient Slavs swathed oaks in cloth and made offerings of kettles, reindeer hide, spoons and other domestic objects. Like the Balts, they sacrificed goats and bulls to Pyorun, the thunder god in his sacred grove. A perpetual fire of oak wood was kept burning before an effigy of Pyorun at Novgorod, and the penalty for allowing the fire to die, was death. Yet, sacred oaks were preserved in Germany into modern times and Russian Orthodox Christians worshipped a holy oak into the 1870s; praying, “Holy oak hallelujah, pray for us.” In the 1917 apparition known as Our Lady of Fatima, when the Virgin Mary, crowned in roses, appeared to Portuguese shepherd children, she was hovering over an oak tree. When a 13th century oak consecrated to Herne the Hunter, was blown down at Windsor in 1863, Queen Victoria led the nation in public mourning.

rnate on Earth in animals and plants, especially trees. In pagan times, no abuse of tree or animal was tolerated. … It was considered sacrilegious to hit the Earth, spit on her or otherwise abuse her.” [6] Yggdrasil, the Norse World Tree, provided a complex template for good and evil, god and man, all that was — and was to be. Perpetual fires blazed before the sacred oaks revered by the ancient Prussians. The ancient Slavs swathed oaks in cloth and made offerings of kettles, reindeer hide, spoons and other domestic objects. Like the Balts, they sacrificed goats and bulls to Pyorun, the thunder god in his sacred grove. A perpetual fire of oak wood was kept burning before an effigy of Pyorun at Novgorod, and the penalty for allowing the fire to die, was death. Yet, sacred oaks were preserved in Germany into modern times and Russian Orthodox Christians worshipped a holy oak into the 1870s; praying, “Holy oak hallelujah, pray for us.” In the 1917 apparition known as Our Lady of Fatima, when the Virgin Mary, crowned in roses, appeared to Portuguese shepherd children, she was hovering over an oak tree. When a 13th century oak consecrated to Herne the Hunter, was blown down at Windsor in 1863, Queen Victoria led the nation in public mourning.

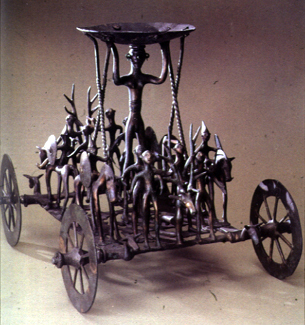

| The ancient Aryan incursions into north India, and the culture these Europeans carried with them are evident in rites like that of Bohemia’s Little Daedala, the observance of which actually appears now, far more “Indo” than “European” to us. In the festival of Little Daedala, boiled meat was set out for birds. When the first raven took some and flew into an oak, that tree was felled. The wood was made into an image and dressed as a bride. Accompanied by dancers, pipers and bridesmaids, the oaken bride was taken with great ceremony to the river and then brought slowly back into the town. The images were saved until the festival of Great Daedala, when they were placed in carts in solemn procession to a mountain, where images, animals and altar were all consumed by fire. Hinducentric as the perambulating oaken bride may seem, she is entirely congruent with the interrelated continuum of European myth cycles and population movements: When Hera left Zeus after one of their interminable fights, he too cut down an oak tree, made an image and dressed it as a bride. In a jealous rage, Hera tore off the bridal veil, but was reconciled to her husband when she saw to what lengths he had gone to win her back. Throughout Europe a goddess image was borne around springtime fields in procession to bring blessings down on the young crops. |  Hallstatt period bronze cult object, Strettweg, Austria, 7th c. BC Hallstatt period bronze cult object, Strettweg, Austria, 7th c. BC |

“The fields were ‘purified’ by either a procession around them or a symbolic passage of the goddess through them. … When the hoe or plow entered the womb of the earth and the seed was sown, a new process of creation was initiated, all under the protection of the grain mother. … With the coming of Christianity, the vast majority of the statues were mutilated: their heads were struck off or their bodies otherwise defaced with a blunt instrument. Many were found in pieces at the bottom of Roman wells, and some were recovered from building foundations where they had been used as masonry blocks. … The struggle against this ancient deity was ferocious.” [7]

Reverence for the oak was a pan-European creed. People who marked solstice and equinox understood that the heavens revolved around the pole star — and pointing forever to that fixed point of light — the celestial axis of their sacred tree. England’s Thor or Thunor, was the Celtic Taranis; Scandinavia’s Thor; the Basque Orko; Germany’s Donar; the Slavic Perun; Greece’s Zeus; and Rome’s Jupiter or Jove. “It is a plausible theory that the reverence which the ancient peoples of Europe paid to the oak, and the connexion which they traced between the tree and their sky-god, were derived from the much greater frequency with which the oak appears to be struck by lightning than any other tree of our European forests. This peculiarity of the tree has seemingly been established by a series of observations instituted within recent years by scientific enquirers who have no mythological theory to maintain. However we may explain it, whether by the easier passage of electricity through oakwood than through any other timber, or in some other way, the fact itself may well have attracted the notice of our rude forefathers, who dwelt in the vast forests which then covered a large part of Europe; and they might naturally account for it in their simple religious way by supposing that the great sky-god, whom they worshipped and whose awful voice they heard in the roll of thunder, loved the oak above all the trees of the wood and often descended into it from the murky cloud in a flash of lightning, leaving a token of his presence or of his passage in the riven and blackened trunk and the blasted foliage. Such trees would henceforth be encircled by a nimbus of glory as the visible seats of the thundering sky-god.” [8]

The oak typically has a very deep central root that plunges straight down beneath the tree. Moreover, hollow, water-filled cells run up and down the wood of the oak’s trunk. This makes the oak better grounded and more conductive than trees with shallow roots and closed cells. Thus, the oak attracts lightning, which passes through to the root; the lightning causes thunder and the connection between the oak and the god of Thunder must have seemed obvious. As the old English saying goes: “Beware the Oak. It draws the stroke”. Nevertheless, the oak is equally the tree most likely to survive such an ordeal; resinous needle bearing trees hit by lightning have a tendency to bake and explode. During the Middle Ages the old tradition of keeping a piece of “survivor” oak in the house to ward off lightning was replaced instead by a frantic ringing of church bells during thunderstorms. Many medieval bells bore the inscription: “Fulgura frango — I break up lightning” Nice theory, but one that proved hazardous in practice: One medieval scholar found that over a 33-year period, 386 lightning strikes on church towers killed 103 bell ringers. As Benjamin Franklin would later observe: “Some people are weatherwise, but most are otherwise”.

The oak typically has a very deep central root that plunges straight down beneath the tree. Moreover, hollow, water-filled cells run up and down the wood of the oak’s trunk. This makes the oak better grounded and more conductive than trees with shallow roots and closed cells. Thus, the oak attracts lightning, which passes through to the root; the lightning causes thunder and the connection between the oak and the god of Thunder must have seemed obvious. As the old English saying goes: “Beware the Oak. It draws the stroke”. Nevertheless, the oak is equally the tree most likely to survive such an ordeal; resinous needle bearing trees hit by lightning have a tendency to bake and explode. During the Middle Ages the old tradition of keeping a piece of “survivor” oak in the house to ward off lightning was replaced instead by a frantic ringing of church bells during thunderstorms. Many medieval bells bore the inscription: “Fulgura frango — I break up lightning” Nice theory, but one that proved hazardous in practice: One medieval scholar found that over a 33-year period, 386 lightning strikes on church towers killed 103 bell ringers. As Benjamin Franklin would later observe: “Some people are weatherwise, but most are otherwise”.

PART II: THE OLD WORLD

| In the best tradition of the early Christian Church, the new religion was routinely grafted onto pre-existing rootstock, while the churches quite literally, built on the energies of place. Most great European cathedrals, including St. Paul’s, Notre Dame de Paris and Chartres, were simply erected on the site of a sacred grove. You need only visit any church of a certain age, Catholic or Protestant, here or in Europe, to confirm that oak leaves, acorns, twigs and tree idols successfully resisted two millennia of Christian tuition to dominate ecclesiastical architecture. Nestled among the gargoyles and grotesques of Europe’s Gothic cathedrals is a ubiquitous man’s head composed of, wreathed by, or sprouting, vines and oak leaves from his mouth. Inside churches this foliate head usually lurks in the darkest corners and most obscure recesses, but he, nevertheless, makes thousands of appearances throughout Europe and the British Isles — and in no fewer than thirty London pubs. Called the Green Man in Britain, Le Feuillou in France, and Blattqessicht in Germany, this protean fellow has undoubtedly wandered even farther afield. Long before he began stealing in amongst the living, this messenger of regeneration and irrepressible life was a fairly common motif on pre-Christian grave markers, some dating to the 4th century BC. A probable remnant of Dionysic and Bacchic mysteries, he is the pollinator: a reminder of godhood in the male, of renewal, and the fact that each of us is finally indivisible from nature. He is associated with Cernunnos, the Horned God Herne, Sir Gawain, Robin Goodfellow, the Lord of Misrule, Puck, John Barleycorn, the King of the Wood, Jack-in-the-Green (the character who dances ahead of the Queen of the May in English folklore), the Garland (the central figure in Central and North European May day celebrations), the earliest incarnations of Robin Hood, Pan, Caesar’s “Dispater”, Morris dancing, and even — the Jolly Green Giant. |  . .  . .  Note sun wheel pendant Note sun wheel pendant |

George Romney, Tate Museum .

| With a noyse and a din, Comes the Maurice-Dancer in |

Although the origins of Morris dancing are lost to us, it’s safe to assume that the jangling of bells, thumping of sticks, and lively tempo of the dance was meant to coax a hibernating earth back to life. A lesser captain of the Golden Hind, (better known as Sir Francis Drake’s ship) Edward Haies, records Morris dancing in what would be Canada as early as 1583, for “the solace of our people, and allurement of the Savages.” Manifests of other ships of the day note that the rather Druidic Morris paraphernalia was routinely ferried to the New World; and Shakespeare makes numerous references to what was evidently regarded as an ancient institution. Today, dancers armed with limp hankies abound, but in our opinion, those outfitted with clashing sticks give real, raucous Morris satisfaction. Much as we may like to dismiss the Morris as a wholesome anachronism, there was a time (not so long ago) when its dark Dionysic roots showed, and the dances notoriously served as a magnet for the worst elements of village life. In fact, the very name “Morris”, may be a derivation of “Moorish” — from the custom of performing in black face to hide “pagan reveller’s” identities from the district priest.

The single-person hobbyhorse, (made of a wickerwork frame with skirt surrounds) as a symbol of youthful male sexuality, was especially given to scandalous misbehaviour. E.C. Cawte described this wanton “Beast of Babylon” in his “Ritual Animal Disguise”, for the the Folklore Society, London: “Whatever their origins, these animals are often unwelcome. … In the Blackburn district ‘Old Ball’ snapped people’s fingers in his jaw when they tried to defend themselves, and sent ladies into hysterics. In Dorset the Pony searched out people supposed to have embarrassing secrets. … Sometimes the horse dashes into the crowd, turns and lifts the back of the hoop, and traps a young woman for a few moments. This used to be supposed to mean a baby within the year, and the significance is still understood. … The horse’s attempt to sit [shrieking women] on his knee could be offensive if it were not for the good nature of the offence and the restraint of the performers.” Some versions feature a “Maid Marion” character, almost always played by a man dressed as woman. Presumably few ladies have been willing to demean themselves since Davenant wrote in 1664: “With the rest of the dancers comes in that ugly carrion, Which country batchelors do call maid-Marrion.” Assorted deaths (including that of the Earl of Rone, who tripped while drunk) were inevitably attributed to the excitement inspired by the lascivious hobbyhorse and frenetic Morris dancers.

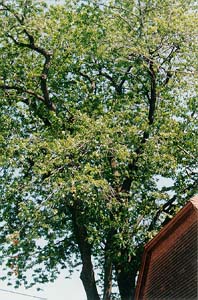

In that tender relationship that existed between man and tree, there was perception that mutual benefits came with mutual generosity: man was not intended to be sole beneficiary. That the oak was a living being was well understood. John Aubrey (1626 – 1697) wrote: “When an oake is falling, before it falls it gives shrieks or groanes that may be heard a mile off, as it were the genus of the oake lamenting.” Special — brutal — punishments awaited the man who presumed to harm a sacred tree. But one wonders how often the legal remedy might have been called upon. The famous avenging power of the oak was formidable and swift, as Aubrey noted: “He who cut a bough in a grove either died suddenly or was crippled in one of his limbs.” Crowned with oak leaves, the ancient Greek woodland spirits, or Dryads, were glad to join in as Orpheus led the oaks in a wild dance down the Pierian mountains, but even these otherwise gentle creatures were notoriously vindictive. In his Metamorphoses, Ovid relates the story of Erysichthon, who scorned the gods and took an axe to Ceres’ grove. As the axe bit into the trunk of a huge oak, “from the heart of the tree, a voice was heard saying: ‘I who dwell within this tree am a nymph, whom Ceres dearly loves. I warn you with my dying breath, that punishment for your wickedness is at hand. … Ceres made the fields tremble, as she devised a punishment to torment him with deadly hunger.” [9] To this day, many Britons consider a coppice which has sprung from oaken stumps as a malign place, best avoided; particularly after dark. Folklorist Ruth Tongue reports that her chauffeur refused to drive past such a one as recently as the 1940s.

In that tender relationship that existed between man and tree, there was perception that mutual benefits came with mutual generosity: man was not intended to be sole beneficiary. That the oak was a living being was well understood. John Aubrey (1626 – 1697) wrote: “When an oake is falling, before it falls it gives shrieks or groanes that may be heard a mile off, as it were the genus of the oake lamenting.” Special — brutal — punishments awaited the man who presumed to harm a sacred tree. But one wonders how often the legal remedy might have been called upon. The famous avenging power of the oak was formidable and swift, as Aubrey noted: “He who cut a bough in a grove either died suddenly or was crippled in one of his limbs.” Crowned with oak leaves, the ancient Greek woodland spirits, or Dryads, were glad to join in as Orpheus led the oaks in a wild dance down the Pierian mountains, but even these otherwise gentle creatures were notoriously vindictive. In his Metamorphoses, Ovid relates the story of Erysichthon, who scorned the gods and took an axe to Ceres’ grove. As the axe bit into the trunk of a huge oak, “from the heart of the tree, a voice was heard saying: ‘I who dwell within this tree am a nymph, whom Ceres dearly loves. I warn you with my dying breath, that punishment for your wickedness is at hand. … Ceres made the fields tremble, as she devised a punishment to torment him with deadly hunger.” [9] To this day, many Britons consider a coppice which has sprung from oaken stumps as a malign place, best avoided; particularly after dark. Folklorist Ruth Tongue reports that her chauffeur refused to drive past such a one as recently as the 1940s.

“The nature of the Celtic temperament is best summed up by the famous Gaulish oath: ‘If I break faith with you, may the skies fall upon me, may the seas drown me, may the earth rise up and swallow me.’ For the Celts, life was a passionate affair, an all or nothing enterprise. This great oath calls the very elements to witness; it also attests to the understanding that the land and the gods are one. This holistic concept of deity is a primal one with which we are out of tune today, secure in the belief that we have ‘conquered’ the elements.” [10] Once, sacred trees were ritually shunned at the moment of their felling; but with expanding Elizabethan ambitions, more and more timber was routinely taken from the Great North Wood — destined for Her Majesty’s shipyards.

| Our worthy forefathers, let’s give them a cheer! To climates unknown did courageously steer Through oceans to deserts, for freedom they came And dying, bequeathed us their freedom and fame Heart of oak are our ships. Heart of oak are our men. |

.

The Battle of Traflagar

Britain’s naval supremacy was purchased at incalculable cost; the amount of oak that went into a ship of the line borders on the incomprehensible. By mid-18th century, when Admiral Lord Nelson’s magnificent HMS Victory was commissioned, it was hewn from a staggering 2,000 oaks — that’s not to dwell on four acres of sail and 27 miles of rigging (thus, “learning the ropes”). Given that the great three-decker consumed 60 acres of forest, little wonder so much guilt attached to the felling of an oak. One ship in Elizabeth’s fleet, which was especially well named the “Revenge”, seemed to impress a malevolent will on all who sailed her: in the course of her career, she delivered the colonists of Roanoke to their New World doom. The Revenge was consigned to a watery grave following a luckless naval engagement with the Spanish.

That’s not to say the mysterious resources of the oak were confined to resentment, reprisal and retaliation. Attributes that we regard now as uniquely Christian — fair play, justice tempered by mercy — were assigned to the oak and appear well established in European folkways long before the old religion was swept away. In the ancient Somerset tale of the Vixen and the Oakmen, a female fox is pursued by hunters all day long. As she fatally tires, the pack of hounds begins to close in. A kindly hawthorn tree points out a tiny break in a stone wall, and suggests that she try to squeeze herself through, but in so doing, she scrapes off most of her shoulder pelt. Terrified and lame though she is, the vixen remembers to thank her benefactor. An instant later, a hound is sniffing around the place in the wall, and as he throws back his head to bay in triumph, the hawthorn drops a cluster of haws down his gullet — leading to a coughing fit instead. “You give her a chance,” the tree admonishes him. “You’re twice her size. She may be a fox, but she has good manners.” The hunters quickly gain again, and the vixen comes upon a huge oak. She begs the tree to open and take her in. “I have news,” she whines. The Oakman is naturally suspicious of vulpine motives, but is, after all, protector of all woodland life. From her new-found sanctuary within the great tree, the vixen relates what she has overheard: the men are planning to cut the oak’s mistletoe bough.

For this intelligence, the angered oak chooses to overlook the geese, ducks and hens that have been disappearing from neighbouring farms, and gently invites her to bathe her lacerated pelt and wipe her sore paws in his oaktree rainpool. She does, and all her cuts and abrasions miraculously heal. When at last she arrives home exhausted, her worried husband brings her a fresh-caught hen and urges her to: “Relax, My Love,” he just wants to hurry back for a goose. It’s a bit of luck, he explains, the men have somehow gotten themselves inextricably tangled up in a holly brake, and the fox husband means to make the most of his opportunities. Here the fox’s base craft is as much to be celebrated as the noble, if vengeful, disposition of the oak. Clearly the (poultry keeping) people who devised such tales were neither simpletons nor sentimentalists.

Not many foxes or other unwary souls lived to relate details of a brush with the Wild Hunt. Led by Wodan, Cernunnos, or Herne the horned god, a deeply rooted race memory of the supernatural Wild Hunt spans European consciousness. Rationally, people living close to the elements might well interpret the violence of spring and autumn gales accompanied by cries of migrating geese as unearthly visitations. But Yuletide stories of the Wild Hunt abound even in Iceland, where there is neither midwinter migration of birds, nor a tradition of the mounted hunt at any season. It may be tempting to explain away the Wild Hunt in neurotic Freudian terms, but the Celtic Encyclopaedia is emphatic: “This deity has far less to do with ‘fertility’ and sexuality than is assumed in popular fantasy, for he is a god of hunting, culling and taking. His purpose is to purify through selection or sacrifice, in order that powers of growth and fertility may progress without stagnation. In this context of purification and depollution, he should be an especially interesting figure to us today, for he represents certain truths known to our ancestors which have been neglected by us at our peril.” It is curious that while this enduring archetype has vanished with the Green Man, story and filmmakers keep the unredeemed, predatory traditions of European werewolf and vampire in active circulation.

Not many foxes or other unwary souls lived to relate details of a brush with the Wild Hunt. Led by Wodan, Cernunnos, or Herne the horned god, a deeply rooted race memory of the supernatural Wild Hunt spans European consciousness. Rationally, people living close to the elements might well interpret the violence of spring and autumn gales accompanied by cries of migrating geese as unearthly visitations. But Yuletide stories of the Wild Hunt abound even in Iceland, where there is neither midwinter migration of birds, nor a tradition of the mounted hunt at any season. It may be tempting to explain away the Wild Hunt in neurotic Freudian terms, but the Celtic Encyclopaedia is emphatic: “This deity has far less to do with ‘fertility’ and sexuality than is assumed in popular fantasy, for he is a god of hunting, culling and taking. His purpose is to purify through selection or sacrifice, in order that powers of growth and fertility may progress without stagnation. In this context of purification and depollution, he should be an especially interesting figure to us today, for he represents certain truths known to our ancestors which have been neglected by us at our peril.” It is curious that while this enduring archetype has vanished with the Green Man, story and filmmakers keep the unredeemed, predatory traditions of European werewolf and vampire in active circulation.

| I ride a horse with foaming mouth and wet forehead, willing ill; flames are in the ends, poison in the middle Njals saga CXXV |

The Wild Hunt was originally made up of slain warriors riding to Valhalla to await the call to take up arms in a final, apocalyptic battle with the forces of destruction. It’s probably redundant to even mention it, but this celebration of the primordial was transformed by a prurient church into a shameless stampede to have sex with the devil and variously recast as the Furious Horde, the Devil’s Hunt, Wütischend Heer, Chasse Artu, Wilde Jagd, the Days of Jupiter, or Mesnie Sauvage. Thus, the exhilaration (although perhaps not to the prey) of sounding horns, baying hounds and the hell bent for leather clatter of galloping hooves striking sparks as foaming mounts carry the old gods to the fore, became just one more terrifying — if routine — threat of abduction by witches, demons, and a very different horned god. Good parishoners knew they were to stay inside; there, they cowered behind locked and bolted doors whispering pious prayers. Parallels with contemporary expressions of political correctitude abound: as early as 4th century Britain, the sons of the Christianizing emperor Constantine were excluding pagans from office, confiscating their lands through an impenetrable system of fines, and successfully put down a pending revolt via “a tidy-minded bureaucrat, an imperial notary who earned the nickname ‘Paul the Chain’ from the paranoid linkage of associations he constructed so as to acquire new victims for his reprisal tribunals.” [11] Plus ca change … But faith was not always sufficient unto the day. In his 380-385 inspection of northern Gaul, St. Martin of Tours made a point of visiting — and demolishing — every pagan shrine he could find; paying most particular attention to the destruction of “wicked” trees. At one stop, local pagans challenged him to perform a miracle: he was more than welcome to cut down their sacred tree if he would stand beneathe as it fell. St. Martin declined the honour and hurried on.

The Wild Hunt was originally made up of slain warriors riding to Valhalla to await the call to take up arms in a final, apocalyptic battle with the forces of destruction. It’s probably redundant to even mention it, but this celebration of the primordial was transformed by a prurient church into a shameless stampede to have sex with the devil and variously recast as the Furious Horde, the Devil’s Hunt, Wütischend Heer, Chasse Artu, Wilde Jagd, the Days of Jupiter, or Mesnie Sauvage. Thus, the exhilaration (although perhaps not to the prey) of sounding horns, baying hounds and the hell bent for leather clatter of galloping hooves striking sparks as foaming mounts carry the old gods to the fore, became just one more terrifying — if routine — threat of abduction by witches, demons, and a very different horned god. Good parishoners knew they were to stay inside; there, they cowered behind locked and bolted doors whispering pious prayers. Parallels with contemporary expressions of political correctitude abound: as early as 4th century Britain, the sons of the Christianizing emperor Constantine were excluding pagans from office, confiscating their lands through an impenetrable system of fines, and successfully put down a pending revolt via “a tidy-minded bureaucrat, an imperial notary who earned the nickname ‘Paul the Chain’ from the paranoid linkage of associations he constructed so as to acquire new victims for his reprisal tribunals.” [11] Plus ca change … But faith was not always sufficient unto the day. In his 380-385 inspection of northern Gaul, St. Martin of Tours made a point of visiting — and demolishing — every pagan shrine he could find; paying most particular attention to the destruction of “wicked” trees. At one stop, local pagans challenged him to perform a miracle: he was more than welcome to cut down their sacred tree if he would stand beneathe as it fell. St. Martin declined the honour and hurried on.

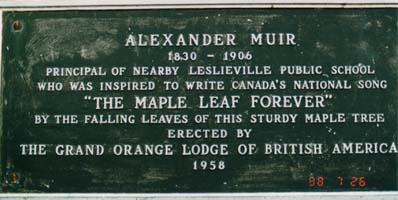

In the event, the church may have triumphed over old sylvan “heathen superstitions,” but, as is often the case, it was not a decisive victory. The persistent belief that water or precious metals may be detected with a wooden divining rod, the custom of the Maypole, the Christmas tree, “knocking on wood” for luck, and many a turn of phrase, can all be traced back to our early reverence for trees. Until recently, when we ourselves became rootless, it was common practice among almost all the European folk to plant a tree to mark a wedding or the birth of a child — and it would be a mistake to assume the tradition has entirely died out. Moreover, as the Christian European church becomes less and less representative of Christian European concerns, trees are being enlisted to take up the old role as intermediary between two worlds; fittingly, to mark our final rite of passage. Eschewing monuments to plant a tree instead, living graves (and a well fertilized tree) are an increasingly common sight in the UK and US. We haven’t been able to discover whether such interments are legal in Canada, but let’s assume they are not. “When the ashes of a Polish freedom fighter and his wife were reinterred in their native village in 1993, two young birch trees, sacred trees in Baltic Paganism, had been planted by the grave. An observer noted that this seemed to be a uniquely Polish mixture of ‘Christian faith, militant patriotism and ancestor worship’. The remains of the General, he thought, were reinterred as if to guard the village and remind its inhabitants of their identity, as ancestral burials always do.” [12] Such a memorial also serves the legendary battle charger, Copenhagen. At the Battle of Waterloo, the Duke of Wellington spent an incredible 18 hours in the saddle of this fearless war-horse. When Copenhagen died after many a long year of cosseted retirement on the Duke’s ancestral estate, he was buried with full military honours — and a sentinel oak (still standing) was planted at the head of this beloved horse’s grave.

| A culture is no better than its woods WH Auden, Shield of Achilles, 1955 |

| Sometime around the mid-19th century, it became apparent that the massive oaken roof beams of the main hall of Oxford’s New College were badly affected by dry rot. Accordingly, a committee was set up to explore the least noxious of available surrogates. Given the enormous size of the beams (forty-five-feet long by two-feet thick) and the prohibitive cost, even then, of oak veneer, replacement was clearly out of the question. In desperation, someone finally suggested inviting the College forester in for a chat. At that, he is supposed to have said: “I was wondering when you’d get around to asking.” Five-hundred years earlier, when the hall was built, a grove of oaks had been planted in the confidence that they would be well and fully grown when the inevitable need for renovations arose. This kind of purposeful prudence goes a long way to redeeming the institution of hereditary privilege; bespeaking a culture worthy of the name. |

As for the larger question: “Were the oaks replanted?” New College itself is blasé about its singular legacy: “It is standard woodland management to grow stands of mixed broadleaf trees; e.g., oaks, interplanted with hazel and ash. The hazel and ash are coppiced approximately every 20-25 years to yield poles. The oaks, however, are left to grow on and eventally, after 150 years or more, they yield large pieces for major construction work.” Each year the College warden inventories properties, including forests the College has owned and managed intelligently, since 1441. When the 16th century Italian poet, Torquato Tasso, wrote Jerusalem Delivered, (an epic poem of the Crusades) he spent the last year of his life waiting for Pope Clement VIII to recognize his achievement. Tasso chose to do his waiting beneath an ancient oak tree near the Vatican. Known as “Tasso’s Oak”, the tree today consists of just one twisted, viable branch, and a dizzying network of iron scaffolding, masonry, beams, girders, bolts and rings clamping the remnants together.

| The planting of trees is the least self-centered of all that we do. It is a purer act of faith than the procreation of children. – Thornton Wilder |

A tree, any tree, is a splendid thing. The restorative powers of resin, that distilled essence of the tree, are justly celebrated. While we are just beginning to chart resin’s anti-bacterial properties, these were well known to the ancient world. In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder devoted most of one book to the problem of wine turning to vinegar. Romans came to add pine and cedar resin to their wines for just this purpose. The only modern carryover of the ancient tradition is Greece’s much-maligned retsina.

Prehistoric resin, or amber, has been traded, coveted and cherished since before recorded time. In 1713, Prussia’s King Frederick William the First authorized construction of an entire room built of amber; later presented to Russia’s Czar Peter the Great, the treasure vanished from sight during the 1945 fall of Königsberg (Kaliningrad). Until very recently, the fate of the amber room was a topic of endless speculation. Long implicated, Stasi (Communist East Germany’s dreaded thought police) involvement seems certain with the recent emergence of a few identifiable pieces Amber is by nature an object of great mystery, and anyone who has worn it will attest to the ineffable sense of well-being it imparts. Tests for authenticity range from the brutal (real amber will not dissolve in acetone) to the arcane (real amber smells fragrant when rubbed energetically against cloth). That small bits of paper or fluff leap to the resulting static charge is old knowledge indeed — the Greek word for amber was Elektron.

Prehistoric resin, or amber, has been traded, coveted and cherished since before recorded time. In 1713, Prussia’s King Frederick William the First authorized construction of an entire room built of amber; later presented to Russia’s Czar Peter the Great, the treasure vanished from sight during the 1945 fall of Königsberg (Kaliningrad). Until very recently, the fate of the amber room was a topic of endless speculation. Long implicated, Stasi (Communist East Germany’s dreaded thought police) involvement seems certain with the recent emergence of a few identifiable pieces Amber is by nature an object of great mystery, and anyone who has worn it will attest to the ineffable sense of well-being it imparts. Tests for authenticity range from the brutal (real amber will not dissolve in acetone) to the arcane (real amber smells fragrant when rubbed energetically against cloth). That small bits of paper or fluff leap to the resulting static charge is old knowledge indeed — the Greek word for amber was Elektron.

| A drop of amber, from the weeping plant, Fell unexpected, and embalmed an ant; The little insect we so much condemn Is, from worthless ant, become a gem. – Martial – Book vi., Epigram xv. |  |

While amber does not quite float in sea water, its light specific gravity makes it a natural voyager, bobbing and tumbling to us through the waves and over the centuries. We can only imagine what these mysteriously radiant gems meant to people who worshipped the sun: “The search for the symbolically important amber was probably one motivating factor [that prompted the early Aryan culture to leave pastoral homelands in the Caucasus] … The sky was the dwelling place of its heroes and deities, and its primary god was the ‘God of the Shining Sky.’ The color of the sun — gold or yellow — had great symbolic importance. Solar patterns — circles, circles with radial lines like the rays of the sun, and crosses — are the most common designs on pottery and bone and amber discs. For Indo-European cultures, gold would be the object of quests, indeed of obsession, during prehistory, during classical times (as attested by the legends of the Golden Fleece and the Argonauts), and certainly into modern times. For [early North European] peoples, gold metal was not the most accessible material that captured the color of the sun. They found their material on the shores of the Baltic Sea. Here, the resins of ancient trees had fossilized to become amber and had washed ashore on the beaches. This semi-transparent, hard substance, in which twigs and insects were sometimes embedded, embodied the color of the sun and held a fascination for these kurganized people. They gathered and carved the amber into discs, cylindrical beads and other jewelry, the most impressive pieces of which were placed in graves with the chiefs.” [13]

In book XVIII of the The Odyssey, Homer refers to “amber beads shining like the sun,” but as Greek fortunes declined, so did their interest in amber. Conversely, Rome’s appetite for amber grew apace with waxing power. Schliemann reported large quantities of amber unearthed at his archeological digs at Mycenae and Troy. The earliest worked pieces of amber (between 11,000 and 9,000 BC) have been recovered from Gough’s Cave, near the Cheddar/Creswell crags in Southern England. Incidentally, Gough’s cave also gave us the palaeolithic “Cheddar Man” — recently linked by mitochondrial (inherited through the mother’s line) DNA to his demonstrated direct descendant Adrian Targett; a shoolteacher living just 100 yards away. (Curiously, while Cheddar Man is described as looking like “any bloke you’d see in a pub”; US authorities insist that Washington State’s Kennewick Man — of the same vintage and initially identified as a Caucasian — simply cannot be classified, and is thus, an Indian.)

As so much else, the Dark Ages eclipsed trade in amber, but by the end of the 14th century, gleaners, craftsmen and merchants alike were operating under the strictest controls – as this 1774 engraving of Baltic collecters working under the shadow of a gibbet makes abundantly clear

Amber trading in the ancient world commenced roughly around 3,000 years BC; certainly, Bronze Age Baltic amber has been found as far afield as Britain, Greece, Egypt, Northern Ireland and Mesopotamia. Pliny’s “Natural History” detailed at length the various myths and legends regarding amber’s origin but he unequivocally stated: “Amber is formed by the pith which flows from trees of the pine species, as a gum flows from cherry trees and resin from pines”. His understanding was to be lost and recovered only 1,500 years later. He also stated that the geographic origin of amber was “in the islands of the north of the Northern ocean that is called Glessum by the Germans”. For this reason when Germanicus Caesar was commanding a fleet in those regions, the Romans gave the name of Glessaria to one of these islands — “Northern Gold”. Photographs exist of the huge “dunes” of crude amber that plagued efforts to recover coal from Germany’s now defunct Bitterfield Mine. While Pliny’s restless curiosity about the natural world dominated European thought for centuries to follow, it was, ironically, his undoing. When Mt. Vesuvius erupted, he hurried there to study the phenomenon at first hand.

Amber trading in the ancient world commenced roughly around 3,000 years BC; certainly, Bronze Age Baltic amber has been found as far afield as Britain, Greece, Egypt, Northern Ireland and Mesopotamia. Pliny’s “Natural History” detailed at length the various myths and legends regarding amber’s origin but he unequivocally stated: “Amber is formed by the pith which flows from trees of the pine species, as a gum flows from cherry trees and resin from pines”. His understanding was to be lost and recovered only 1,500 years later. He also stated that the geographic origin of amber was “in the islands of the north of the Northern ocean that is called Glessum by the Germans”. For this reason when Germanicus Caesar was commanding a fleet in those regions, the Romans gave the name of Glessaria to one of these islands — “Northern Gold”. Photographs exist of the huge “dunes” of crude amber that plagued efforts to recover coal from Germany’s now defunct Bitterfield Mine. While Pliny’s restless curiosity about the natural world dominated European thought for centuries to follow, it was, ironically, his undoing. When Mt. Vesuvius erupted, he hurried there to study the phenomenon at first hand.

He was overcome by fumes, and died on August 24, AD 79 — the day Pompeii and Herculaneum were entombed. Amber has a refractive index (that is, the level at which light is bent as it passes through it) of 1.54. That index remains fairly constant regardless of type or place of origin. Art historians have long lamented a fundamental decline since the days of the Renaissance and Baroque, but on closer inspection it appears that, quite independent of ability, the works of the Old Masters acquired their luminous depths through the application of varnishes high in crushed amber content. In reality, their mediums were varnishes, not oils as we know them today. The rich, lustrated effect was achieved by mixing drying oils, such as linseed or walnut, with tree resins and balsams at very high temperatures — with amber the most desirable addition of all. As the Industrial Revolution approached, the risk of fire prompted commercial paint manufacturers to switch entirely over to cold processes, and thus, today’s uniformly opaque product. “To make a painting with an everlasting varnish … make your picture on a clay surface that is well glazed and very smooth … and then varnish it with oil of walnut and amber.” [14]

The presence of succinic acid in Baltic amber, but unknown in any living species of pine, led to the conclusion that the “amber tree” must have been the long extinct Pinites Succinifer. The discovery of Pseudolarix Pine — containing succinic acid and still growing on China’s eastern mountain ranges — may now supplant older assumptions. Strangely, Pseudolarix pine cones trapped in fossil resin have also been discovered on Axel Heiburg Island in Canada’s high Arctic. Frequently present in true Baltic amber are tiny star-like hairs which are released by oak buds during their early growth; another reminder of the archaic pedigree of the oak tree. “Entomologist David Grimaldi of New York City’s American Museum of Natural History has announced a find he calls ‘scientifically the most important of all amber fossils. ‘It’s three tiny flowers, probably from an oak tree, that date to the age of the dinosaurs, some 90 million years ago. That makes them the oldest intact flowers ever found in amber, and an important clue to the origin of the flowering plants that now dominate the earth.'” [15]

The presence of succinic acid in Baltic amber, but unknown in any living species of pine, led to the conclusion that the “amber tree” must have been the long extinct Pinites Succinifer. The discovery of Pseudolarix Pine — containing succinic acid and still growing on China’s eastern mountain ranges — may now supplant older assumptions. Strangely, Pseudolarix pine cones trapped in fossil resin have also been discovered on Axel Heiburg Island in Canada’s high Arctic. Frequently present in true Baltic amber are tiny star-like hairs which are released by oak buds during their early growth; another reminder of the archaic pedigree of the oak tree. “Entomologist David Grimaldi of New York City’s American Museum of Natural History has announced a find he calls ‘scientifically the most important of all amber fossils. ‘It’s three tiny flowers, probably from an oak tree, that date to the age of the dinosaurs, some 90 million years ago. That makes them the oldest intact flowers ever found in amber, and an important clue to the origin of the flowering plants that now dominate the earth.'” [15]

Earliest representation of the mythical amber tree, from ‘Hortus Sanitatus’ 1491

| For there is hope of a tree, if it be cut down, that it will sprout again, and that the tender branch thereof will not cease – Job 14: 7 |

When scientists began to properly inventory the equipment of Ötzi, the 5300-year-lost Alpine “Ice Man”, they found 18 different trees represented among his meagre possessions. His longbow and axe handle were made of Yew. (The copper axe head was a revelation in itself: dismissed at first as trade goods, arsenic deposits in Ötzi’s hair indicate that he had smelted the metal himself. Prior to this, Europe’s Copper Age was presumed to have dawned a thousand years later.) The handle of his small dagger was Ash. Lime bast (the bark of the tree) was twisted into incredibly strong cords. His backpack frame consisted of Hazel with Larch supports. Leaves of Norway Maple insulated the embers he carried in a container along with leaves of Juniper. For fuel he carried Reticulate Willow, Green Alder, Norway Spruce, Pine and Elm. His arrow shafts were made of Viburnum and Cornus (Cornelian Cherry or Dogwood). These arrows, by the way, were ballistically more sophisticated than we might expect of late Stone Age technology. The flights (feathers) applied in a spiralling form, stabilized the spinning arrow to ensure accuracy over some considerable distance — the same principle as the rifling in gun barrels. An exhaustive series of autopsies performed on Ötzi revealed embarrassing Trichuris trichiura eggs, or whipworm — but once

When scientists began to properly inventory the equipment of Ötzi, the 5300-year-lost Alpine “Ice Man”, they found 18 different trees represented among his meagre possessions. His longbow and axe handle were made of Yew. (The copper axe head was a revelation in itself: dismissed at first as trade goods, arsenic deposits in Ötzi’s hair indicate that he had smelted the metal himself. Prior to this, Europe’s Copper Age was presumed to have dawned a thousand years later.) The handle of his small dagger was Ash. Lime bast (the bark of the tree) was twisted into incredibly strong cords. His backpack frame consisted of Hazel with Larch supports. Leaves of Norway Maple insulated the embers he carried in a container along with leaves of Juniper. For fuel he carried Reticulate Willow, Green Alder, Norway Spruce, Pine and Elm. His arrow shafts were made of Viburnum and Cornus (Cornelian Cherry or Dogwood). These arrows, by the way, were ballistically more sophisticated than we might expect of late Stone Age technology. The flights (feathers) applied in a spiralling form, stabilized the spinning arrow to ensure accuracy over some considerable distance — the same principle as the rifling in gun barrels. An exhaustive series of autopsies performed on Ötzi revealed embarrassing Trichuris trichiura eggs, or whipworm — but once  again, he was carrying two Birch galls (Piptoporus betulinus) which contain oils toxic to parasites and laxative compounds that would cause expulsion of the dead and dying worms and their eggs. [16] Before we dismiss this ancient Tyrolean as a grunting sub-human, we might remember that at any given moment, an estimated two-thirds of the present world population is suffering parasitic infections. Ötzi, at least, had the wherewithal to recognize and treat his malady. What were at first taken to be rather unsophisticated tattoos (bars, crosses and parallel lines concentrated at his joints and along the lower spine) prove to be rather surprising “evidence that Europeans practised acupuncture some 2,000 years before the Chinese. ‘It looks like an early form of acupuncture originated in central Europe,’ said Dr. Frank Bahr, president of the German Academy for Acupuncture. … ‘I was amazed, 80 per cent of the points correspond to those used in acupuncture today.’ … ‘These points would still be selected by the best acupuncturists,’ Bahr said.” [17] Thus, Ötzi enjoyed the best medicine of his day — and the worst of ours. This minimalist from the past has unwittingly fuelled an exploitative dance macabre. Following a bitter custody dispute, he has been installed in the Museo Archeologico dell’Alto Adige, in Bolzano, Italy. Who says Americans are gauche? Here, consumer-ghouls can slake their thirst for Ötzi backpacks, Ötzi note-pads, Ötzi fanny-packs, Ötzi mouse pads, Ötzi pins, Ötzi badges, Ötzi baseball caps, Ötzi T-shirts, Ötzi key rings, Ötzi cigarette lighters, Ötzi chocolate cadavers (tarted-up in a red bow-tie and straw-boater), Ötzi pizza, Ötzi ice cream, Ötzi ice wine, Ötzi iced tea, and don’t forget the Ötzi wurst! Wurst of all, some loathsome new life form is actually buying this crap.

again, he was carrying two Birch galls (Piptoporus betulinus) which contain oils toxic to parasites and laxative compounds that would cause expulsion of the dead and dying worms and their eggs. [16] Before we dismiss this ancient Tyrolean as a grunting sub-human, we might remember that at any given moment, an estimated two-thirds of the present world population is suffering parasitic infections. Ötzi, at least, had the wherewithal to recognize and treat his malady. What were at first taken to be rather unsophisticated tattoos (bars, crosses and parallel lines concentrated at his joints and along the lower spine) prove to be rather surprising “evidence that Europeans practised acupuncture some 2,000 years before the Chinese. ‘It looks like an early form of acupuncture originated in central Europe,’ said Dr. Frank Bahr, president of the German Academy for Acupuncture. … ‘I was amazed, 80 per cent of the points correspond to those used in acupuncture today.’ … ‘These points would still be selected by the best acupuncturists,’ Bahr said.” [17] Thus, Ötzi enjoyed the best medicine of his day — and the worst of ours. This minimalist from the past has unwittingly fuelled an exploitative dance macabre. Following a bitter custody dispute, he has been installed in the Museo Archeologico dell’Alto Adige, in Bolzano, Italy. Who says Americans are gauche? Here, consumer-ghouls can slake their thirst for Ötzi backpacks, Ötzi note-pads, Ötzi fanny-packs, Ötzi mouse pads, Ötzi pins, Ötzi badges, Ötzi baseball caps, Ötzi T-shirts, Ötzi key rings, Ötzi cigarette lighters, Ötzi chocolate cadavers (tarted-up in a red bow-tie and straw-boater), Ötzi pizza, Ötzi ice cream, Ötzi ice wine, Ötzi iced tea, and don’t forget the Ötzi wurst! Wurst of all, some loathsome new life form is actually buying this crap.

PART III: THE NEW WORLD

A tree, any tree, is a splendid thing. Homer said: “As the leaves of trees, so are the of men.” Living beings that have witnessed the rise and fall of civilizations are rightly deserving of our best efforts to protect them. More immediately, as Ötzi well knew, trees are also invested with a largesse of pharmacological and physical properties. Every tree has its virtue, and it’s just not true that the only trees “worth saving” are in far off rainforests: the virulently toxic Yew yields a breakthrough in cancer research, thus redeeming an age-old association with death and mourning. The humble Pussywillow has recently been appropriated by Indian supremacists to advance an increasingly familiar argument: aboriginals introduced the white man to “Willow magic”; prior to this selfless act of kindness, salicin or salicylic acid (synthesized finally into aspirin) was unknown to Europeans. Sad to say, some sources actually suggest that the now ubiquitous White Willow (the readiest source of salicin) was an Old World introduction to North America. Be that as it may, salicin was certainly known to, and recorded by, Hippocrates in 200 BC, Dioscorides in 100 AD, and Galen in 200 AD.

A tree, any tree, is a splendid thing. Homer said: “As the leaves of trees, so are the of men.” Living beings that have witnessed the rise and fall of civilizations are rightly deserving of our best efforts to protect them. More immediately, as Ötzi well knew, trees are also invested with a largesse of pharmacological and physical properties. Every tree has its virtue, and it’s just not true that the only trees “worth saving” are in far off rainforests: the virulently toxic Yew yields a breakthrough in cancer research, thus redeeming an age-old association with death and mourning. The humble Pussywillow has recently been appropriated by Indian supremacists to advance an increasingly familiar argument: aboriginals introduced the white man to “Willow magic”; prior to this selfless act of kindness, salicin or salicylic acid (synthesized finally into aspirin) was unknown to Europeans. Sad to say, some sources actually suggest that the now ubiquitous White Willow (the readiest source of salicin) was an Old World introduction to North America. Be that as it may, salicin was certainly known to, and recorded by, Hippocrates in 200 BC, Dioscorides in 100 AD, and Galen in 200 AD.

| He who plants a tree Plants a hope…. Canst thou prophesy, thou little tree, What glory of thy boughs shall be? … Gifts that grow are best; Hands that bless are blest; Plant! life does the rest! – Lucy Larcom |  |

It is virtually impossible to place a monetary value on the many vital services that trees provide, but the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection tried. By their (1994 US-dollar) reckoning, a single tree will contribute services worth nearly $200,000 over the course of a 50-year lifetime. This includes providing oxygen ($31,250), recycling water and regulating humidity ($37,000), controlling air pollution ($62,500), producing protein ($2,500), providing shelter for wildlife ($31,250), and controlling land erosion and fertilizing the soil ($31,250). As for the pleasure of escaping the heat of the day to daydream beneath the frothy canopy of a blossoming tree, swinging on a rope swing, picking the season’s first batch of cherries, listening as your children play in a treehouse, or watching birds nesting in a sapling you planted, no dollar value has ever been assigned. Since the 1940s, California has lost more than a million acres of woodland. Population growth — and the inevitable suburbanization that accompanies it — is expected to devour another quarter million oak-covered acres by the year 2010. As elsewhere, California can thank unchecked immigration for the congestion. Just to keep up, the state must now build a new school every 24 hours. Hey, whatever. In 1954, a micro-manager, appropriately named Brown, estimated that if humans would just learn to subsist on glop pumped out of algae farms and yeast factories, the planet might yet sustain 50 billion people. [18]

It is virtually impossible to place a monetary value on the many vital services that trees provide, but the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection tried. By their (1994 US-dollar) reckoning, a single tree will contribute services worth nearly $200,000 over the course of a 50-year lifetime. This includes providing oxygen ($31,250), recycling water and regulating humidity ($37,000), controlling air pollution ($62,500), producing protein ($2,500), providing shelter for wildlife ($31,250), and controlling land erosion and fertilizing the soil ($31,250). As for the pleasure of escaping the heat of the day to daydream beneath the frothy canopy of a blossoming tree, swinging on a rope swing, picking the season’s first batch of cherries, listening as your children play in a treehouse, or watching birds nesting in a sapling you planted, no dollar value has ever been assigned. Since the 1940s, California has lost more than a million acres of woodland. Population growth — and the inevitable suburbanization that accompanies it — is expected to devour another quarter million oak-covered acres by the year 2010. As elsewhere, California can thank unchecked immigration for the congestion. Just to keep up, the state must now build a new school every 24 hours. Hey, whatever. In 1954, a micro-manager, appropriately named Brown, estimated that if humans would just learn to subsist on glop pumped out of algae farms and yeast factories, the planet might yet sustain 50 billion people. [18]

| When green buds hang in the elm like dust And sprinkle the lime like rain Forth I wander, forth I must And drink of life again – AE Housman |

City dwellers (unlike their dogs) think of trees just twice a year. Right on schedule, each spring and fall, even the most neglected roadside drab manages to dazzle us anew. Trees are okay. We like trees. Trees are nice to have around, but evidently not nice enough for us to notice when a month of drought quietly kills one just outside the door. Unaccustomed as we are to thinking about this blessedly undemanding population, we are wholly unprepared when trees meet other enduring human preoccupations.

The Celts saw the salmon as the wisest of creatures. This knowledge (acquired feeding on the oak’s acorns fallen into a sacred pool) is given flesh as the vigorous salmon vaults the waterfall — perfectly mirroring the intuitive leap of an agile brain. “One of the most extraordinary things to contemplate is that as we think and make associations, our brains actually make connections and grow physically! The more we use our brain, the more dendrites (the ‘arms’ between brain cells) are grown, and the more synaptic connections are made (connections from the end of one dendrite to another). These neural pathways are called dendrites because they look like the branches of a tree, and dendrite is Greek for ‘tree-like’. Photographs of sections of the cerebral cortex look like photos of a thicket of trees in winter. So as we imagine a sacred grove of trees in our minds and work with it over many months to create a network of associations, we are literally building a thicker, richer complex of connections at a physical level in our brains, as well as a structure on a subtler level in the psyche which can connect our conscious self with our unconscious self.” [19]

| Making a famine where abundance lies, Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel. – Shakespeare |

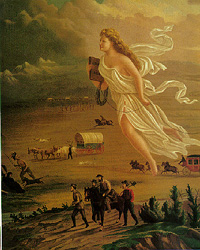

Seldom have greed and incompetence found more congenial accommodation than right here in Canada. Our entire history may be read as a headlong rush to realize maximum profit before devouring the goose that laid the golden egg. As ever, Canada’s error is not unique; our ignorance only makes it seem so. Raubwirtschaft (the exploitation of resources for a distant population) leads to The Tragedy of the Commons (too many people in pursuit of too few resources prefaces total collapse). A hat trick of human greed, unregulated access, and a supine or complicit regime, offers absolutely no incentive to leave anything for those doomed to follow. No resource is really “infinite”; from today’s perspective greed on such a grand scale borders on the incomprehensible, but consider: what is the interminable abuse of our refugee system, our honesty, kindness, charity, compassion, generosity — gullibility — by a seemingly endless stream of self-proclaimed refugees and migrant opportunists, but the utterly ruthless exploitation of the latest in a long line of Canada’s similarly “infinite” resources? Under the tyranny of two-fisted government (that’s one in your pocket and the other waving a cudgel over your head) today’s newcomer is spared anything so infra dig as drawing a living from treacherously icy Atlantic waters, tramping remote trap lines, clearing homestead lands, providing for his own family, or even learning the language. “Well, you’re here now — now here’s your cheque”. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word “exploit” as utilizing: “for one’s own ends,” and with a humorous nod to all that folding money, it comes from the Latin, meaning “frequently” and “unfold”. Doubt it? “The wholesale defrauding of our refugee system represents an unnecessary expenditure of $1.25-billion per year.” [20] “Between 1996 and 1998 approximately 15 per cent of immigrants to Canada were refugees.” [21]

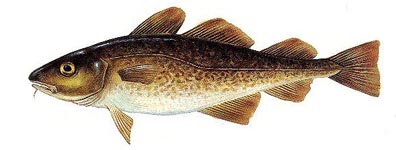

In 1497, John Cabot remarked the “infinite” number of codfish that actually impeded the progress of the ‘Matthew’ through the Grand Banks. A surviving letter of the day notes: “The sea there is swarming with fish which can be taken not only with the net but in baskets let down with a stone, so that it sinks in the water.’ … The coast of North America was churning with codfish of a size never before seen and in schools of unprecedented density. … Englishmen wrote of catching five-foot codfish off Maine, and there are persistent accounts in Canada of ‘codfish as big as a man’. In 1838, a 180-pounder was caught on Georges Bank, and in May 1895, a six-foot cod weighing 211 pounds was hauled in on a line off the Massachusetts coast. Cabot’s men may well have been able to scoop cod out of the sea in baskets”. [22] By the 1550s, the Newfoundland cod trade supported hundreds of ships and thousands of men travelling annually between Europe and the outports. In due course, all the world would make its way to our waters for a portion. Canada’s notorious inability to “just say no” to foreigners persisted well beyond the killing spike of 1968; the date from which Cod stocks began a steady precipitous decline. Thanks to spectacularly poor management our unimaginably “infinite” cod fishery collapsed and closed in 1992.

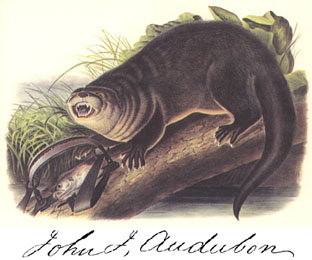

The unlovely Codfish. Without food, his like will not be seen again. Despite extermination of the Atlantic Cod and extirpation of the Pacific Salmon — Canada’s fishery exports last year were the highest on record .

| When the last individual of a race of living things breathes no more, another heaven and another earth must pass before such a one can be again. – William Beebe |

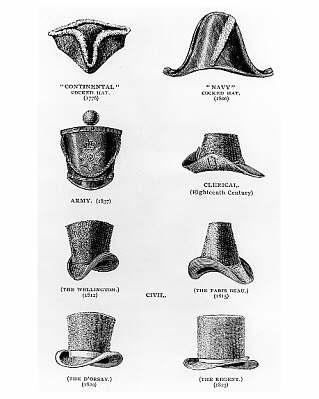

A similarly “infinite” supply of boreal animals and the usual prospects of wealth brought French and English to what was then essentially just a big company town — Rupert’s Land. The presence of some of these same fur-bearing creatures on Canada’s shamefully extensive lists of dead and dying animals may be felt as a reproach and one more tragedy of the Commons. Many have said that Canada was built on the back of the beaver: fuelled by “a small and frivolous item: the beaver hat. From the early 17th Century to the middle of the 19th, no proper European gentleman appeared in public without one. …

A similarly “infinite” supply of boreal animals and the usual prospects of wealth brought French and English to what was then essentially just a big company town — Rupert’s Land. The presence of some of these same fur-bearing creatures on Canada’s shamefully extensive lists of dead and dying animals may be felt as a reproach and one more tragedy of the Commons. Many have said that Canada was built on the back of the beaver: fuelled by “a small and frivolous item: the beaver hat. From the early 17th Century to the middle of the 19th, no proper European gentleman appeared in public without one. …

In 1760 alone, the Hudson’s Bay Company exported to England enough North  American beaver pelts to make 576,000 hats. … By the 1830s, splashes of ornamental furs — not only beaver, but marten, fox and otter — were appearing on the collars, sleeves, hems, gloves and boots of ladies and gentlemen alike.” [23] But ten years earlier, during the 1820s, sea otter populations were already in their final stage of collapse. The denouement of the beaver must have been even more dramatic; they “began to decline in numbers as early as 1638. … With the use of steel traps, trapping became more and more effective. By 1812 beavers were scarce everywhere in Canada east of the Rocky Mountains. … Shortly after the turn of the century beavers became scarce in western Canada.” [24] In 1793, David Thompson worried: “Every intelligent Man saw the poverty that would follow the destruction of the Beaver, but there were no Chiefs to Controul it.” [25] “One [HBC] factor, located in an area with only one tribe, actually purchased the safety of the beaver lodges by giving ‘debt’ to the Indians for leaving them alone.” [26] “According to Paul Le Jeune, a Quebec Jesuit missionary in the 17th century, when the Innu found a beaver lodge, they ‘kill[ed] all, great and small, male and female.’