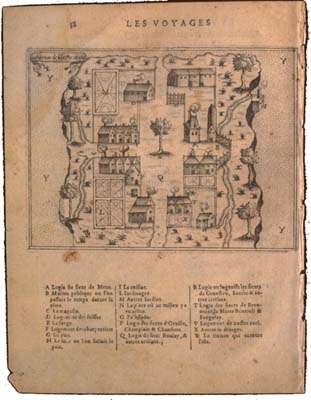

Canadensium plantarum historia, 1635 Canadian botanical in 1635, he need hardly have misplaced his pince-nez. Thanks to their efforts, M. Cornut was able to describe the subjects of his Canadensium plantarum historia without troubling to venture anywhere near Canada. The disproportionate number of North American wildflowers classified today as “Canadense” or “Canadensis” stand as an enduring tribute to Jesuit industry. Robins follow the 35-degree isotherm north, because at 35 degrees Fahrenheit, earthworms reach the surface of the thawing ground. A map of Champlain’s 1604 settlement at Isle Sainte-Croix on the Bay of Fundy shows that gardens were an immediate consideration.

Canadensium plantarum historia, 1635 Canadian botanical in 1635, he need hardly have misplaced his pince-nez. Thanks to their efforts, M. Cornut was able to describe the subjects of his Canadensium plantarum historia without troubling to venture anywhere near Canada. The disproportionate number of North American wildflowers classified today as “Canadense” or “Canadensis” stand as an enduring tribute to Jesuit industry. Robins follow the 35-degree isotherm north, because at 35 degrees Fahrenheit, earthworms reach the surface of the thawing ground. A map of Champlain’s 1604 settlement at Isle Sainte-Croix on the Bay of Fundy shows that gardens were an immediate consideration.

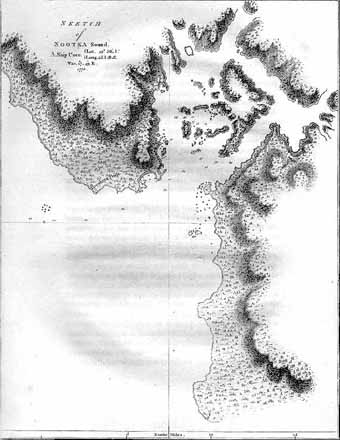

While that settlement failed, his Quebec colony would boast a botanical garden. Canada’s oldest surviving garden, the walled enclosure at St. Supician Seminary on Montreal’s Notre Dame Street, dates from the 1680s. By the 1670s, even the rude forts and outposts of the Hudson’s Bay Co. were planting English greens. Cape Breton’s Fortress of Louisbourg 18th century formal potager gardens are still open to the public.  Maps of the day depicted the bulk of the country as a great unmarked hinterland. On British maps, this terra incognita terminated with New Albion (British Columbia). Spain and Russia had poked about the area in a desultory kind of way; but British ascendency was established in the spring of 1778 by a man who had already made immense contributions elsewhere. Captain James Cook came out of retirement to seek the fabled North-West passage. It was to be his third, and fatal voyage. This venture brought together an otherwise familiar cast of historical figures. His midshipman was a 19-year-old officer cadet named George Vancouver; his sailing master a 21-year-old perfectionist named William Bligh. As the young Cook had in his day charted the Newfoundland coastline, so Bligh charted – accurately – the Alaskan waters where the Exxon Valdez was to run aground 200 years later.

Maps of the day depicted the bulk of the country as a great unmarked hinterland. On British maps, this terra incognita terminated with New Albion (British Columbia). Spain and Russia had poked about the area in a desultory kind of way; but British ascendency was established in the spring of 1778 by a man who had already made immense contributions elsewhere. Captain James Cook came out of retirement to seek the fabled North-West passage. It was to be his third, and fatal voyage. This venture brought together an otherwise familiar cast of historical figures. His midshipman was a 19-year-old officer cadet named George Vancouver; his sailing master a 21-year-old perfectionist named William Bligh. As the young Cook had in his day charted the Newfoundland coastline, so Bligh charted – accurately – the Alaskan waters where the Exxon Valdez was to run aground 200 years later.

Resolution and Discovery at Nootka Sound During his first voyage to the South Seas, Cook’s scientific team had collected 30,000 specimens.

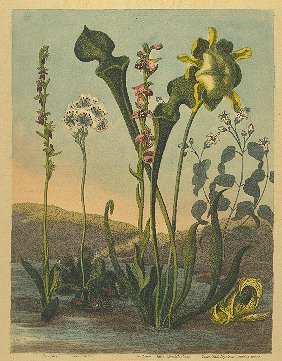

The effect of introducing 1,400 entirely new plant species to a world where only 6,000 had previously been known was to accelerate knowledge of the natural world by 25 per cent in just three years. That deluge of information almost certainly contributed to the formulation of Thomas Malthus’ 1798 theories, which in turn inspired Charles Darwin. The chief botanist on Cook’s first voyage — Joseph Banks — typified the spirit of his times. While he was certainly driven by scientific curiousity, Banks proved an equally tireless promoter of commercial applications for these newly described botanicals. Men like Banks and Cook represented the best European spirit

Joseph Banks during the great exploration: curious, courageous, enterprising and inventive. As a member of the Royal Society, Banks had the requisite clout to not only introduce tea as a cash crop to India, but to commission HMS Bounty to transport breadfruit for cultivation from Tahiti to the West Indies. In a further twist of fate, it was Banks again who had recognized Australia’s potential as a great open-air prison. He presented a paper to Parliament outlining his ideas in some detail. Following the mutiny on the breadfuit-laden Bounty, the same William Bligh was appointed governor to the fledgling New South Wales penal colony. He held the post for three years — and then his prisoners mutinied. No wonder a mother bear with cubs is dangerous. She gives birth during deepest hibernation and wakes to find that she has been feeding voracious offspring ever since.

Joseph Banks during the great exploration: curious, courageous, enterprising and inventive. As a member of the Royal Society, Banks had the requisite clout to not only introduce tea as a cash crop to India, but to commission HMS Bounty to transport breadfruit for cultivation from Tahiti to the West Indies. In a further twist of fate, it was Banks again who had recognized Australia’s potential as a great open-air prison. He presented a paper to Parliament outlining his ideas in some detail. Following the mutiny on the breadfuit-laden Bounty, the same William Bligh was appointed governor to the fledgling New South Wales penal colony. He held the post for three years — and then his prisoners mutinied. No wonder a mother bear with cubs is dangerous. She gives birth during deepest hibernation and wakes to find that she has been feeding voracious offspring ever since.  Under gruelling conditions, New World plants were constantly being catalogued, collected, and laboriously transported back to England. In February of 1825, following an eight month voyage out, David Douglas found himself deposited at the mouth of the Columbia River. The Royal Horticultural Society had been well advised to place their trust in the indomitable Mr. Douglas. He would prove very much equal to the task of examining the area supporting the most living matter per hectare in the world — New Albion’s coastal rain forest. When he started back on March 20, 1827, he chose an overland route that took him by foot over the Rocky Mountains, and from there via canoe, to York Factory on the shores of the Hudson Bay. Incredibly, when he left for England on October 11, both he and his plant specimens were still alive. Known to us for his “Douglas” fir, it was his introduction of the flowering currant that more than subsidized the entire expedition. Douglas was to meet an untimely end on the same Hawaiian island that had claimed the life of Captain Cook.

Under gruelling conditions, New World plants were constantly being catalogued, collected, and laboriously transported back to England. In February of 1825, following an eight month voyage out, David Douglas found himself deposited at the mouth of the Columbia River. The Royal Horticultural Society had been well advised to place their trust in the indomitable Mr. Douglas. He would prove very much equal to the task of examining the area supporting the most living matter per hectare in the world — New Albion’s coastal rain forest. When he started back on March 20, 1827, he chose an overland route that took him by foot over the Rocky Mountains, and from there via canoe, to York Factory on the shores of the Hudson Bay. Incredibly, when he left for England on October 11, both he and his plant specimens were still alive. Known to us for his “Douglas” fir, it was his introduction of the flowering currant that more than subsidized the entire expedition. Douglas was to meet an untimely end on the same Hawaiian island that had claimed the life of Captain Cook.

Captain Cook “In the evenings we wandered through the woodland paths, beneathe the glowing Canadian sunset, and gathered rare specimens of of strange plants and flowers. Every object that met my eyes was new to me, and produced that peculiar excitement which has its origin in a thirst for knowledge and a love of variety.” (Susanna Moodie, 1832)  Of the 4,200 plant species growing in Canada today, only about 1,000 have been introduced. As the nation was settled, Canada continued to produce an improbable number of people eager to inventory our wealth of coastal, alpine, prairie, woodland, maritime and Arctic plants. With few exceptions, when Europeans settled here, it was for life. The seeds they brought with them nourished spiritual as much as physical needs. Pioneer gardens quickly grew into living reminders of a world that was lost to them forever. Among rose growing circles, there is a famous story of a woman who had emigrated out from G

Of the 4,200 plant species growing in Canada today, only about 1,000 have been introduced. As the nation was settled, Canada continued to produce an improbable number of people eager to inventory our wealth of coastal, alpine, prairie, woodland, maritime and Arctic plants. With few exceptions, when Europeans settled here, it was for life. The seeds they brought with them nourished spiritual as much as physical needs. Pioneer gardens quickly grew into living reminders of a world that was lost to them forever. Among rose growing circles, there is a famous story of a woman who had emigrated out from G ermany with a cherished piece of rootstock from her mother’s favourite rambling rose. Map of Cook’s third voyage Impressive – National Geographic North American medicinal plants Flora Danica Köhler’s Medizinal Pflanzen, 1887 Nicholaus Culpeper’s complete 17th century herbal Encyclopaedia of plants – (common-Latin converter) Mostly Canadian garden links information – extensive Red Wigglers – the Cadillac of worms Canadian Rockies wildflowers Bluebird numbers have fallen by 90% in some places Easy solutions from “The Bluebird Trail”

ermany with a cherished piece of rootstock from her mother’s favourite rambling rose. Map of Cook’s third voyage Impressive – National Geographic North American medicinal plants Flora Danica Köhler’s Medizinal Pflanzen, 1887 Nicholaus Culpeper’s complete 17th century herbal Encyclopaedia of plants – (common-Latin converter) Mostly Canadian garden links information – extensive Red Wigglers – the Cadillac of worms Canadian Rockies wildflowers Bluebird numbers have fallen by 90% in some places Easy solutions from “The Bluebird Trail”

On the voyage to America 12 children were born, of which all but one died. Of the above 262 souls embarked, 53 died on the ocean and the remaining 221 landed safely at Halifax. There were 183 freights and 53 bedplaces. From the 8th of July 1752 to the 28th of February 1753, 83 persons from the above-mentioned ship died in Halifax. We were 14 days travelling down the Rhine and 14 weeks on the ocean, not counting the time we were on board the ship in Rotterdam and again in Halifax before we were put to ashore, all of which amounted to 22 weeks. – Excerpt from Johann Michael Schmitt’s Bible, as translated by Winthrop Bell. A “freight” was a full-fare passenger – everyone over a certain stipulated age, which varied from time to time or ship to ship, but was frequently 14 years.

Infants (usually under the age of 4) were carried free and no space allocation was made for them. Children between those ages were accounted “half-freights.” Thus: Mr Schmitt meant by the numbers of adults and of children (on the GALE from Rotterdam leaving Leymen for America on 9 May 1752 and docking in Halifax on 8 June 1752) were such that the 262 “souls” amounted to 183 “freights”. The still extant ship’s manifest shows that there were actually 249 “souls” and 183 “freights”. The “bedplaces” were subdivisions of the ‘tween decks space in the ship, to which the emigrants were assigned. There were certain regulations with respect to these.

The minimum “bedplace” size was supposed to be 6 feet square, and no more than 4 “freights” were to be assigned to any one “bedplace.” On John Dick’s ships the “bedplace” sizes were somewhat larger than the legal minimum. Mr. Schmitt’s statement means that the GALE’s emigrants had somewhat more room than they would have had the ship been filled. – Lunenberg County, Nova Scotia genealogy discussion list