…………

………… ……….

……….

Long before he’d run to lard and ladies, England’s King Henry VIII wrote a book decrying the excesses of the German monk, Martin Luther. For this act of piety, a grateful pope conferred on him the never-to-be-relinquished title — “Defender of the Faith”. It is one of history’s little jests that Henry’s own excesses would indirectly serve to export Luther’s Reformation around the globe.

While Luther embodied the courage and independence of mind that survives in the best of us, he is nevertheless an abiding enigma. The man who would reshape all Christendom — and with it, our very understanding of freedom and dignity — saw himself not as reformer or free thinker, but as God’s most obedient servant. This perception would prove no impediment when he resolved, as an ordained priest, to marry a nun and father six children. Despite the demanding personal itinerary, Luther made the time to harry and humiliate the world’s most powerful institution, at the height of the Inquisition.

Anything but conciliatory in trouble, this most unrepentant and quarrelsome of trouble-makers managed not just to cheat the flames, but to die peacefully in bed, steps from the house where he had been born sixty-two years earlier — cursing the Pope with his dying breath. Possessed of a brutally incisive mind, he tapped into the wants of the age, and asked searching questions the intervening 500 years have never quite resolved. Helped along by Luther’s exertions, a protesting Europe was dragged into the modern era, and it is not too far-fetched to say that if you are reading this as a European in North America, he played some part in it. Like any other idea whose time has come, Luther’s revolution simply could not be contained within the precincts of Church or disputation hall: in the end, his would be a Reformation within the very hearts and minds of men.

How many valiant men, how many fair ladies, breakfast with their kinfolk and the same night sup with their ancestors in the next world! – Giovanni Boccaccio

When Martin Luther was born, near midnight on 10 November 1483, his was an essentially Mediaeval world, beset by terrors, tortures, superstitions, witch hunts, executions, slave raids, aftershocks of plague, climate changes, crop failures, famine, gouging taxation, mandatory tithing, war, and civil war. Albrecht Dürer’s “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” and the surreal horrors of Hieronymous Bosch are portals to that desperate age: rightly was the Dance of Death a universal theme. In 1240, Mongols sacked Kiev, Christendom’s easternmost city. Jerusalem fell four years later. Constantinople, eastern bastion of Christianity for a thousand years, was lost in 1453. Corsairs traded European slaves from Mediterranean ports. Wearing the red fez that signified it had been dipped in Christian blood, the Ottoman Turks of Suleiman the Magnificent would not be turned back until they reached the gates of Vienna.

For all that, the known world was small and bounded by regions of which little was known, apart from the recurrent warning: “Here be dragons.” One such killer was imported from China: the Black Death sundered European civil life and cast a pall over the dawning light of the Renaissance. Nearly ten-million people a year died between 1347 and 1351, and sporadic outbreaks of plague would persist until the close of the 17th century. Ferdinand and Isabella launched their Inquisition three years before Luther’s birth; and, overlooking this garden of infinite suffering was a cruel God who had sacrificed His only Son. Little wonder then, that the continent’s most popular book was the macabre “Ars Moriendi — The Art of Dying”. This morbid tome addressed the one thing the average man might hope to exert a degree of influence over: the manner of his dying. Catastrophic infant mortality rates and the prevalence of changeling superstitions saw the new-born Luther rushed to baptism on the very next day — the feast of St. Martin.

Had he been born in England, where primogeniture obtained, we might never have heard more of Luther; but the local custom was ultimogeniture, and the youngest son (not he) would inherit.

G.E. Rost, Traditional Dress of the Mining and Metalurgical Workers in the Kingdom of Saxony, Ca. 1830

Within weeks of Luther’s birth, his father Hans, (also an unpropertied elder son) descended into the copper mines. A lifetime of the hard work, thrift, prudence and self-improvement that would hallmark the Protestant ethic made of Hans Luther a propertied entrepreneur and elected city councillor. At first, leasing a small smelting furnace, he would eventually own two foundries outright and acquire rights to half a dozen mining shafts. A difficult and opinionated man, Hans had Martin’s life neatly mapped out for him from the beginning.

Two years before Columbus’ historic voyage, seven-year-old Martin was sent to study at the local Latin school. At thirteen, he commenced studies with the lay Brethren of the Common Life; it was almost certainly here that he absorbed the central tenets of all his subsequent teachings — informality and piety. A gifted student when literacy rates ran at just 10%, Luther matriculated, and moved on to acquire a master’s degree at age 21. His father had prescribed a career in the law for him, and these pronouncements were rigidly unassailable. Then, one fine summer’s day, a bolt from the blue would fix Luther’s life-long pattern of doing exactly the most unexpected thing imaginable. After a visit home, a nearby lightning strike hurled him to the ground. Calling on St. Anne to save him, he vowed: “Ich will ein Mönch werden” — I will become a monk.

To the Councilmen of all Cities in Germany that they Establish and Maintain Schools: “A town does not thrive in that it accumulates immense treasures, builds sturdy walls, nice houses, many muskets and suits of armour alone. On the contrary, a towns best and most prosperous progress, welfare and strength, comes from having many excellent, educated, decent, honest and well brought-up citizens.” (Luther 1524)

The same exacting standards he brought to everything applied in the selection of a monastic order. Luther settled on the Augustinians as the order best qualified to meet his academic and ascetic criteria, and, over his father’s furious objections, the lavishly educated 21-year-old turned his back on the world, and entered the cloister at Erfurt in 1505. Ordained in 1507, Luther’s diligence and intelligence so impressed his superiors that they sent him on to the University of Wittenberg. There he joined the senate of the theology faculty, earned his D.Th. in 1512, and met the man who would be steadfast friend, inspiration, and mentor — his vicar — Johann von Staupitz. In 1514, at 30, Luther was appointed vicar of Wittenburg city church, and by next year, as district vicar, he oversaw eleven Augustinian monasteries scattered throughout Meissen and Thuringia.

A lesser man might have made a life and reputation of all this, but Luther craved a spiritual dimension rarely encountered in administrative affairs. His spiritual turmoil, or anfechtungen, and growing discontent likely dated from a 1511 pilgrimage to Rome, when, as a young priest, he had hiked 800 miles over the Alps to see the Holy City for himself. It was like an immovable object meeting an immovable object. Luther found, not the hallowed utopia of his imaginings, but a crumbling and profanely foetid Mediaeval city inhabited by thieves, cut-purses and prostitutes, of whom — he wryly noted — a good number inhabited the ecclesiastic palaces. Touts and hustlers lay in wait for pilgrims at city gates, and the Forum served as combination cow pasture and homeless doss. Classical statuary was routinely burned and ground for building lime.

To the idealistic young German, the entrenched commercialism of the Holy City was crass beyond endurance: “Passa, passa — Get on with it!” the Roman priests prompted as their stolid northern brother lingered over mass. Paid masses were a lucrative industry — sometimes seven in the course of an hour! The tally did not escape Luther’s increasingly critical eye. Irreverently bawdy retellings of pope and prelate’s sordid exploits scandalized him almost as much as the purported deeds themselves. In his unprevaricating Luther way, he would later say he was glad he had seen Rome with his own eyes; otherwise, “I might have been afraid of being unjust to the Pope.” During Luther’s visit, Michelangelo lay lost to this world, creating a cosmos on the ceiling of St. Peter’s while the Basilica grew up all around him. It was this, indirectly, that would draw Luther from the shadows of academe and into harm’s way.

As the coin in the coffer rings, so the soul from purgatory springs!

Given the always murky financial and political finagling of the Papal Curia, the decision, in 1507, by Pope Julius II to build St. Peter’s was proving a ruinously expensive disaster. His successor, the pampered second son of Lorenzo (the Magnificent) de Medici, said, on his election: “Let us enjoy the papacy, since God has given it to us!” As a great patron of the arts, Pope Leo X ran through the Vatican treasury in just two years. Faced with insurmountable debts at usurious rates, the Church sought salvation in a catalogue of reprehensible schemes: spurious offices went to the highest bidder, and a brisk trade in jubilees, relics and indulgences ensued.

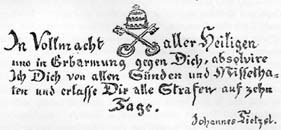

The purchase of a letter of indulgence was essentially a spiritual shortcut, and the thinking went like this: Christ and the saints had built up an infinite reservoir of merits, and the pope could draw from this spiritual treasury — for a price. In the hands of less than scrupulous friars, indulgences (particularly the much-needed and widely-advertised St. Peter’s indulgence of the early 1500s) proved a popular palliative, and one that spared busy parishioners’ confession, good works, and even genuine contrition. Our own poor buy state-sponsored lottery tickets: indulgences provided post-retirement insurance for the hereafter. Doubtless a stroke of fiduciary genius, the selling of indulgences was nevertheless condemned by Canon Law as the sin of Simony — the attempt to profit from the selling of Divine grace. It is only fair to mention that the indulgence was also an important — albeit clumsy — step from Mediaeval to modern sensibilibities: it was an early attempt to exact payment as punishment for sin in lieu of suffering, as fines would supplant corporal punishment (incidentally, a pre-Christian Germanic legal concept — “wergeld”).

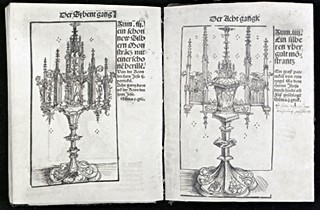

The Heiltumbuch of All Saints Church, Wittenberg, Lucas Cranach, 1510. This book served as a museum catalogue for pilgrims viewing the relics on display at Wittenberg. This page shows two reliquaries (containers). In 1510, the display of the relics took place on 14 April, and the book was probably on sale that very day. Frederick the Elector had been on pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1493, and a single thorn from Jesus’ crown of thorns formed the centrepiece of a collection that comprised 19,013 pieces by 1520. Praying before each of these implied a general-absolution of 1,902,202 years! |

Despite his disapproval of the trade in relics and indulgences, it’s worth noting that Luther’s university, even his own salary, were funded in part by offerings of the pious as they prayed before Frederick’s “wunderkammer” of relics. In the end, though, the sale of indulgences, the unrestrained greed, bilking marketing methods, fear advertising and carnival barker atmosphere would unloose the full sinew of Luther’s formidable scorn. Seething with rage, he watched as his parishioners made their way through market-day crowds, only to be accosted by one Johann Tetzel. From a gaudy pulpit, the Dominican friar (and part-time papal inquisitor) exhorted simple folk to pay heed to the agonized screams of their beloved parents as they begged for release from purgatory. Why not spare Mother and Father further torment and buy one of his letters of indulgence? Confronted by the lurid spectacle, Luther must have felt that all the venalities of “that Disordered Babylon” (as he called Rome) had followed him home.

Behold, I have set before thee an open door and no Man can shut it – Revelation 3:8.

We like to imagine Luther a Mediaeval Dirty Harry, nailing his 95 theses to the Wittenberg Castle Church door with a gun-butt, challenging the Church to “make his day”. As is often the case; the truth is considerably more complex, if less dramatic: Luther had been questioning indulgences from his very first lecture at Wittenberg University. Moreover, at that time — October 31, 1517 — those Church doors served as the university bulletin board. It was, therefore, the most natural thing in the world for the head of the theology department to invite colleagues to debate scores of sore-points the people had been grumbling about for a hundred years. It was widely felt that Germany was little more than a hardworking milch-cow, ill-used by a distant and debased Rome. At the renewal of the St. Peter’s indulgence, rulers all over Europe had protested that their economies simply could not survive the drain of funds to Rome. As a compromise, Pope Leo X allowed almost everyone — except Luther’s ruler, Frederick — to pocket a portion of the proceeds. By this machination, this form of commission kickback on papal fundraising, Frederick, had in effect, been coerced into subsidizing his neighbour, Albrecht of Mainz’s, purchased bishopric. But in 1517, Luther still believed that mountebanks like Tetzel (peddling indulgences under Albrecht’s direction for six months by then) were anomalies; and if the poor Pope only knew of the improprieties committed in his name, “He would prefer to have St. Peter’s collapse in ruins than build it with the skin and flesh and bones of his sheep.” Thus would Luther, in all innocence, ignite a long-readied fuse. His treatise began: “Out of love and zeal for the elucidation of truth,…”

| To repress these arguments and scruples of the laity by force alone, and not to resolve them by giving reasons, is to expose the Church and the Pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to make Christians unhappy – the 90th point in the 95 theses |

So, the stage was set for Luther’s own rude awakening and Frederick’s later resolve to safeguard his vexatious priest. Reading over the posting, a colleague told Luther: “You tell the truth, good brother, but you will accomplish nothing.” Another said, “They will not stand for it.” To which Luther replied: “But what if they have to stand for it?” As for Tetzel, when he read the theses, he crowed: “Within three weeks I shall have this heretic thrown into the fire.” But it was not to be. Within the month, without Luther’s knowledge or permission, translated reprints would electrify all Europe, “as if the angels themselves were messengers.” If the explosive speed of the shockwave that raced across Christendom caught Rome off guard, imagine the effect on an obscure academic who just wanted to debate some theological irregularities. For the reforming monk and his ideas, the time had come.

King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia commissioned the 95 theses to be inscribed on bronze replacement doors when Luther’s were lost in a 1760 fire

Although Luther’s world laboured under burdens we can barely imagine, it’s chilling to think that the state of free speech was more assured in the age of Inquisition than in a society forever patting itself on the back for its purported “tolerance”. At Wittenberg University, debate was seen as essential to the educated mind: disputation sharpened dialectic and rhetorical skills, aided memory, and served to clarify issues of moment. Our own academics — so broad of beam, narrow of mind and risk averse — might blush if they could only remember how. In those days, coming up with a hundred arguments to prove a point was a common student assignment.

It should be emphasized that the university did not just pay bonuses to faculty participating in such debates; it also levied fines against those who absented themselves! The university debates provided an important part of the town’s recreation, with disputation halls often packed to suffocation. These debates were part instruction, part entertainment for a broad cross-section of society, and, incidentally, were carried on so passionately that it was not unheard of for one or another participant to take a poke at the nose of his opponent. From there, the townsfolk rehashed the issues for weeks in market and fishmongery. Into this climate of robust inquiry was born the original information revolution. A modified wine press would disseminate the intellectual treasures of the Reformation, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Great Explorations, along with a wealth of scientific, medical and technical advances. Rightly did Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) say, “If I have seen farther, it is because I stood on the shoulders of giants.”

God’s last and greatest gift

The earliest surviving piece of printing that can be confidently attributed to Johannes Gutenberg — a calendar — dates from 1448. It has been estimated that, in 1450, Europe contained less than 100,000 books: by 1500, more than nine million! Like an explosion in a typesetting shop, in just fifty years, “the names of more than 1000 printers, mostly of German origin, have come down to us from the fifteenth century. In Italy, we find well over 100 German printers; in France, 30; in Spain, 26.” (“The Catholic Encyclopaedia”, Volume VII) If Rome lost some ground to the printed word, it was nevertheless gracious and good-hearted in its beleaguered state — pronouncing the new technology “a divine art”. Gutenberg records print runs of 200,000 letters of indulgence at a time. When the Vatican recently made public the contents of the Third Miracle of Fatima, it employed yet another emerging technology, the Internet. It is interesting (in light of the so-called Internet Problem) to remember that, in 1513, the Paris guild of illuminators sued the printers for loss of work. They were not gratified in their action. From 1517, when he first began to write for the public, until his death, Luther wrote an average of a book a fortnight: in fact, during the first ten years of the Reformation, Luther alone wrote one-quarter of all books published in Germany. He called the press “God’s last and greatest gift.” Yet, being Luther, he was not so dazzled that he might overlook shoddy craft: “I wish I had sent nothing in German! It is printed so poorly, so carelessly and confusedly, to say nothing of the bad type faces and paper.

I shall send nothing more until I have seen that these sordid money-grubbers, in printing books, care less for their profits than for the benefit of the reader!” Care for his fellow man was a constant: Luther tirelessly championed universal literacy and man’s right to discuss — independent of priests, interpreters, intermediaries and experts — those issues that most affected him. The Reformation was the crucial turning-point in the history of literacy; with women (as primary teachers of the young) most particularly encouraged to read. Luther advocated the still-radical idea that the common man is perfectly capable of doing his own thinking, reaching his own conclusions and living accordingly; and Gutenberg’s “artificial writing” machine broadcast the seditious seed. By 1523, Luther’s works had romped through 1,300 printings — a half million copies.

Luther had several things going for him, including secular rulers who, quarreling with Rome, were prepared to take the home-grown genius under a protective wing. The Holy Roman Empire was a strange political-religious amalgam: Roman by heritage, Christian by faith, primarily German by language, culture, and location. With over 300 separate principalities, duchies, landgravates, and free cities under his titular control, the Holy Roman Emperor wielded unchecked authority only on his own ancestral estates. The real powers behind the throne were the seven Electors (Luther’s protector, Frederick was one of these) who ruled important territories, and, according to German custom, elected the emperor. Despite this curious arrangement, Luther’s survival depended largely — on Luther. What set him apart from other reformers, and there had been many, was a unique set of character flaws: pig-headed, combative, blisteringly abrasive, having once formulated his theses, he neither wavered nor backed down. As the biting invective grew more violent, bystanders must have wondered whether he was entirely sane, but, as his very rare admissions of fear indicate, his courage was of an order that still inspires, half a millenium later.

|

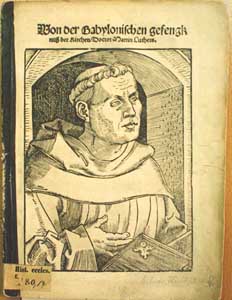

I hear a report that fresh bulls and papal curses are being prepared against me, by which I am urged to recant, or else to be declared a heretic. If this is true, I wish this little book to be a part of my future recantation, that they may not complain that their tyranny has puffed itself up in vain. –

“On The Babylonian Captivity Of The Church”, 1520 |

He had no patience with those “monks and priests, snoring in their deep-rooted ignorance” who would perpetuate an erring system, whether through sloth, greed, or fervent belief, mattered not in the least once he had prescribed so clear a course of treatment. Naturally, the Church had no inclination to do this rude upstart’s bidding. Frustrated, Luther exploded: “Why do we not seize, with arms in hand, all those evil teachers of perdition, those popes, bishops, cardinals, and the entire crew of Roman Sodom? Why do we not wash our hands in their blood?” When he realized the extent to which a thirsting Europe was hanging on his every word, he softened his rhetoric for fear of sparking a conflagration: “I should not like to see the Gospel defended by force and bloodshed.”

His plain speaking endeared him to an almost wholly agricultural people: he certainly never muttered “fertilizer” if he meant to say “shit”. Luther’s purported “scatological obsessions” have been a bone for detractors to maul and slobber over from his time to ours, but on closer inspection, his “crude” insights are sophisticated and irresistible. For Luther, as for all Christians of the day, the Devil was no mere abstraction. In a 1515 sermon to the Observant Augustinians, Luther identified slander as the Devil’s preferred field of operation. As a matter of fact, he said, the real meaning of the word “Satan” is backbiter; the shitter on God and man. Venturing where angels still fear to tread, Luther identified the latrines as the customary abode of slander — a region long-identified with the Devil. Luther’s own claim, that his initial revelatory insight came to him while “on the cloaca,” has been mocked for centuries. But in the context of his day, it was a stunningly potent theological concept. At the expense of his own dignity, he clearly implies that there is no place and no human condition, however debased, that is beyond God’s reach. Less rude than rudimentary, such ideas would be immediately accessible to peasant congregations.

As a trained theologian, Luther dipped from many wells. It is curious that he maintained a life-long antipathy to St. Thomas Aquinas, when Aquinas’ Summa Theologica sounds as though it might have been written by Luther himself: “A tyrannical government is not just, because it is directed, not to the common good, but to the private good of a ruler. Consequently, there is no sedition in disturbing a government of this kind, unless indeed the tyrant’s rule be disturbed so inordinately that his subjects suffer greater harm from the consequent disturbance than from the tyrant’s government. Indeed, it is the tyrant rather that is guilty of sedition, since he encourages discord and sedition among his subjects, that he may lord over them more securely; for this is tyranny, since it is ordered to the private good of the ruler and to the injury of the multitude.”

As his personal animus to Tetzel the indulgence peddler indicates, Luther loathed bullying of any kind, fervently believing that it was words and ideas that swayed men’s minds, not threats of punishment. That attitude extended beyond mere powers of the state to maim and kill: he felt that man must come to God too, out of love for a good and beneficent Creator, not through menaces of eternal torment. “God wants that people do not despair of danger and fear.” Much like ours, his was a world dominated by a doctrine of love and tolerance that had hardened into Inquisition. In many ways, Luther was a supremely modern thinker; modern enough to shame some present-day inquisitors — serving, as they do, all the gods of political correctitude with every lawful pricking instrument. He argued that heretics must be refuted with words, not with fire, “else, the hangmen would be the most learned doctors in the world.” He deplored the idea of a cruelly judgemental Heavenly Father quite as much as his severe terrestrial one. Why, he wondered, would a God of Love be more inclined to condemn than to show tenderness and mercy? “We have made of Christ a task-master far more severe than Moses.”

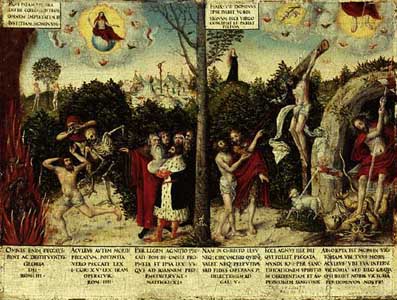

– Lucas Cranach, (Luther’s friend and neighbour) Law and Gospel 1551

It must have been a plague sent by God, that induced so many people to accept such lies – Luther

Gone forever, the respectful monk who would rather die than offend the Pope. At first ignored, then ridiculed and finally bullied, Luther had come away from preliminary examinations at Augsburg convinced that the pontificate connived in the abuses of pia fraus (pious frauds) like Tetzel. It really was a spectacularly corrupt climate: Luther and Niccolo Machiavelli were contemporary writers, and observed in their own disparate ways, identical abuses. Luther’s work would become a series of firebrands tossed into the papal court; calculated to insult as much as incite. Suppose the Pope did enjoy jurisdiction over the realm of purgatory (as imputed to him by the indugence vendors) why not empty it forthwith in an act of simple Christian charity? If the Pope loved St. Peter’s, oughtn’t he to pay for it himself, rather than bleeding his flock? These errors indicated that the Pope was fallible — beneathe, and not above — the Word of God. For that matter, how could a God of unbounded goodness be bribed to release souls from purgatory? Luther loathed, too, the globalist tendencies he saw in the Church, and perceived money and capital transactions as fundamentally inhuman, (“he who touches money, touches dirt”) realizing profit at the expense of human beings. He thought men might create an economic system which would preserve God’s Creation and allow people to live together in a self-determined manner. Being intimately familiar with the development of both the mining and banking systems, he was far from naive about putting money out to breed: of usury, he said: “the Devil is in that game.”

Once he hit his stride, he was absolutely relentless: the Communion cup should be shared with the congregation, and not restricted to the clergy alone. Let the people pray in a language they understand (both reforms would come 450 years later to the Catholic Church, at Vatican II, 1962-1965). Let men and women lift up their voices to praise God with hymns in the churches. He wrote dozens of hymns for his congregations, a liturgical innovation that laid the foundation for church music and influenced worship throughout the Protestant world. Church finances should be the particular responsibility of each individual country — not of Rome. If priests insisted on interpreting the Gospel as a business venture, men should equally insist on reading the Word of God for themselves. Each man’s relationship with his God was surely a profoundly personal matter, and that made the imposition of elaborate ritual, foreign tongues and dogma tyrannical. Man could find forgiveness outside of the Church; Liberty was an essentially spiritual — and not a political state. “The Christian is the lord of all, and subject to none … servant of all, and subject to every one.” The monasteries should be reduced in number, and converted into schools where students were free to come and go. Christians and their Pope should do good works for their own sake, not to accrue merit. He called for the abolition of pilgrimages, private masses, veneration of relics, mendicancy, (“each town should support its own poor, and not allow strange beggars to come in”) indulgences, interdicts, and saints’ days. Extreme unction (the sacrament of the last rites), said he, was unscriptural, and should be renounced. Luther said what everyone else was thinking about priestly celibacy: that leaving a housekeeper alone with a man “is like bringing fire and straw together.” Priests should marry, or not, just as they pleased. Marriage was a civil matter, to which the Church might add a blessing if it wanted. He condemned the maze of byzantine regulations confronting those who would divorce.

In the contest between Luther and Tetzel, the latter comes off very badly indeed. One hopes his indulgences bought him some consideration: within two years of locking horns with Luther, death would pretty effectively neutralize Tetzel. It is a measure of the man that Luther sent a letter of comfort as his old opponent lay dying. Luther is much the more complex of the two — a curious blend of sympathy for his suffering people and lion-hearted Christian soldier. By now, he fully expected to be condemned on earth. Confronted with the very real prospect of the stake, his courage seemingly never failed him: “Let them freely go to work, Pope, bishop, priest, monk, or doctor: they are the true people to persecute the truth, as they have always done.”

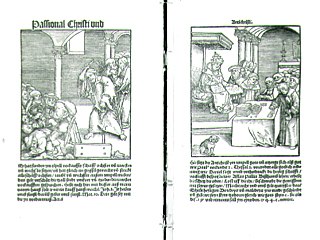

The Passion of Christ and Antichrist – 1521 – Lucas Cranach’s book of 13 opposing woodcuts represents one of Luther’s key concepts: on this page, Christ drives the money-changers from the temple; opposite, the Pope hands out letters of indulgence for profit.

Luther simply wouldn’t shut up; in his Address to the German Nobility, 1520, he rails: “The custom of kissing the Popes feet must cease. It is an un-Christian, or rather an anti-Christian example, that a poor sinful man should suffer his feet to be kissed by one who is a hundred times better than he. If it is done in honour of his power, why does he not do it to others in honour of their holiness? Compare them together: Christ and the Pope. Christ washed his disciples feet, and dried them, and the disciples never washed his. The Pope, pretending to be higher than Christ, inverts this, and considers it a great favor to let us kiss his feet.” Then, “The Pope is not satisfied with riding on horseback or in a carriage, but, though he be hale and strong, is carried by men like an idol in unheard-of pomp. I ask you, how does this Lucifer-like pride agree with the example of Christ, who went on foot, as did also all his apostles?” He concludes: “If this is not Antichrist, I do not know what it is.” Not surprisingly, Rome reopened the Inquisition against him that year.

Both Luther and the Church performed at their very best when they were defining the perceived idiocy of the other’s position. As the flames drew ever nearer, Luther only grew ever more obdurate. Over the objections of the people, his books were burned in Cologne that November. A month later, the final bull of excommunication arrived. “Exsurge, Domine” (“Arise, Oh Lord. Judge your cause for a wild boar ravages thy vinyard …” in spirited reference to the Saxon monk) was the last bull addressed to Latin Christendom as an undivided whole, and the first to be disobeyed by a large part of it. The bull directed all princes, magistrates, and citizens, on threat of excommunication and promise of reward, to seize Luther and his followers; to hand him over to the apostolic chair. Every house and community that harboured him or his followers was threatened with the  interdict (refused the consolations of religion). Christians were forbidden to read, print, or publish his books, and commanded to burn them. Under the circumstances, who but Luther would respond by arranging a very public bonfire to burn the papal document instead?

interdict (refused the consolations of religion). Christians were forbidden to read, print, or publish his books, and commanded to burn them. Under the circumstances, who but Luther would respond by arranging a very public bonfire to burn the papal document instead?

Efforts to enforce this unpopular decree inspired obstructive behaviour as it moved north. It met with determined resistance at Meissen, Merseburg, and at Brandenburg. At Leipzig, papal representatives were insulted and the bull was torn to pieces in the ensuing scuffle. It was worse at Erfurt: papal messengers were mocked and ridiculed; an openly contemptuous theological faculty refused to publish any part of it and the bull was tossed into the river. In a day when the Church had the power, and the will, to consign heretics to the stake, these were no mere acts of defiance, but deliberate provocations. Luther must surely have remembered (he was a boy of fifteen at the time) what had happened to a Florentine reformer. Girolamo Savonarola was excommunicated in 1497, and consumed by his own Bonfire of the Vanities the following year. Luther confessed to a friend later, that he was nearly frozen with terror at the enormity of his disobedience as he burned his writ of excommunication. Yet, as the flames took the bull, he sang out: “Farewell, unhappy, hopeless, blasphemous Rome! The wrath of God has come upon you as you deserved.”

Peace if possible, but truth at any rate. – Luther Peace if possible, but truth at any rate. – Luther |

In spite of his fear, he leapt to every challenge, not just with spirit, but with spite. In an early series of published dialogues, he advised one of the Vatican’s most learned theologians “not to make himself any more ridiculous by writing books.” Another had withdrawn in disgust, stating that he was “unwilling to dispute any further with that deep-eyed German beast filled with strange speculations.”

Luther the provocateur complained that he felt “more acted upon than acting … I cannot control my own life … I am driven into the middle of the storm … It was the love of truth that drove me to enter this labyrinth and stir up six hundred minotaurs,” (sentiments all too familiar to those who fall afoul of contemporary inquisitors). The next year, 1521, Leo X proclaimed Henry VIII, Defender of the Faith, while Luther’s effigy burned with his books in Rome’s Piazza Navona. Luther’s good friend, the vicar Johann von Staupitz, was advised to restrain him or face dismissal. Staupitz resigned in disgust. Consumed with his pleasures, the Pope comprehended this “monkish squabble” in remotest Saxony as little as the man behind it. Consistently dismissive, Leo X had at first waved off the “drunken German who wrote the Theses; when sober, he will change his mind.” Still later; wasn’t it simpler to remove the critic rather than correct the abuse? If the man was pining for recognition, why not offer him a cardinal’s hat — or apply a little pressure. That the Pope should think so indicates how little he knew of his adversary. |

The Papacy And Its Divisions, Hans Sachs, Nuremberg, 1526 – preface by Martin Luther

A new Holy Roman Emperor had been elected in 1520. (Luther’s ruler, the Elector Frederick, had been offered, but declined, the imperial crown.) Raised on jousting matches and tales of the Crusades, the young Charles V, the Most Christian King of France, saw himself as the very flower of chivalry. Calling himself God’s standard-bearer, he is best remembered for “landing near Carthage with a fleet, capturing Tunis and Goletta in July, 1535, and liberating nearly 20,000 Christian slaves.” (“Catholic Ecyclopaedia”, volume XV) Almost from the moment of Charles’ sovereignty, Aleander, the papal nuncio, was agitating for Luther’s removal: “Nine-tenths of the people are shouting ‘Luther!’ and the other tenth ‘Death to the Roman Court!’ In such a manner, does the Saxon dragon raise his head; in such a manner, do the Lutheran serpents multiply and hiss far and wide.”

It was certainly true that at least some aspect of the movement to reform resonated at every level of German society. In 1500, 90 per cent of the German population worked the soil. It could not escape their attention that fully one-third of German lands were owned by the Church. The Lateran Council of 1517 (the year Luther posted his theses) allowed the Pope to collect one-tenth of all the ecclesiastical property of Christendom. A nascent national consciousness grated at a papal bureaucracy dominated by Italians, Frenchmen and Spaniards.

Mediterraneans had worn out their welcome in North Europe. In 1521, the German princes sent Charles 102 “oppressive burdens and abuses imposed on and committed against the German empire by the Holy See of Rome.” Foremost among these was the issue of a papal “monarch” exercising unjust authority within the German states. The Pope sold posts to unqualified candidates while others still occupied them — a high Church office might “go” for the modern-day equivalent of $250,000. If a German cleric died in, or en route to, Rome, the papacy confiscated his benefice and office. Another abuse was the transfer of lawsuits from German to Roman courts; that is, German ecclesiastical princes could force laypeople to stand trial in church courts under threat of excommunication. Students were rioting all over Germany. What was worse, they were burning anti-Luther publications. Clearly, something had to be done. Ninety years after Joan of Arc died at the stake, 37-year-old Luther was summoned to appear before the 21-year-old Charles at the 1521 Diet of Worms.

Hier stehe ich! Ich kann nicht anders, Gotte helfe mir!

It makes good art, but for all his unbridled defiance, it is unlikely Luther would have postured thus before Charles V at Worms. Contemporaries report that, as was customary, Luther faced his inquisitors from a penitent kneeling position.

When the Emperor and his retinue arrived in Worms, they found themselves in the midst of Luthermania: poems, cards, placards, pictures of Luther, and stacks of his banned books were being openly traded everywhere. When Luther entered the city of his reckoning, the crush of cheering springtime crowds made for an odd sort of triumphal procession. The elegant young Emperor looked on the unprepossessing object of adulation before him and said: “This man will never make me a heretic!” For his part, Luther welcomed the opportunity to clarify some of his more difficult concepts. Instead, he was shown a stack of 20 of his books and asked if he would retract all his works and publicly recant the heresies they contained. Dumbfounded, he asked for time to deliberate. The next day he appeared before the assembled lords and said: “I do not accept the authority of popes and councils who contradict each other. Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason, I cannot and will not recant anything since it is neither right nor safe to act against conscience. Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me!”

As he left the room, he told a supporter, “I am finished!” The next morning, Charles rendered his decision: “I am descended from a long line of Christian emperors. A single friar who goes counter to all Christianity for a thousand years must be wrong. I will have no more to do with him.” Luther was condemned as a heretic and an outlaw and sent on his way with a letter of safe conduct, or Schutzbrief — good for 21 days. In 1414, the Reformer Jan Hus had been similarly summoned, condemned, and issued a letter of safe passage, but Hus was seized on the spot and burned at the stake. Charles would not stain his knightly honour in condemning an errant priest outright, but the Edict of Worms (drafted by Aleander) branded Luther the devil incarnate, whose “teaching makes for rebellion, division, war, murder, robbery, arson, and the collapse of Christendom.” On expiry of Luther’s letter of safe conduct, he was fair game: if he should happen to be murdered (hint, hint), so be it; his assassin would be neither sought nor punished.

The Elector flanked by his Reformers: Luther, Philipp Melanchthon, Erasmus, Zwingli, et al Be a sinner and sin stoutly, but more stoutly trust and rejoice in Christ. – Luther, letter to Melanchthon

Now the Elector Frederick stepped in. In the aftermath of Luther’s excommunication, Frederick had quietly consulted Erasmus of Rotterdam, to ask his opinion of Luther’s “crimes”. Erasmus (no fan of Luther’s) gave it as his judgment, that Luther had “touched the triple crown of the Pope and the stomachs of the monks.” Hardly a Canadian politician, Frederick “was not one of those who would stifle changes in their very birth;” after the Edict of Worms, he arranged to have Luther whisked away in a mock abduction. As his life depended on it, Luther was lost from view for the better part of a year. Rumours flew that he had been set upon and killed, but nothing now could stop events he had set in motion. From time to time disquieting news reached Luther in his exile; the Reformers were pushing ahead at a reckless pace and were splintering into dozens of sects. In his colourful phrase: “no one knew who was the cook and who the ladle.” He wrote: “Good Lord! Will our people in Wittenberg give wives even to the monks? They will not push a wife on me!” (In the event, they wouldn’t have to).

While momentum carried his Reformation forward, he lived quietly, as Junker Georg, in Wartburg Castle high in the Thuringian Forest. The gentler side of the man is evident when he records his enjoyment of the singing birds, “sweetly lauding God day and night with all their strength.” Exulting in the beauty of the nighttime sky: “He who has built such a vault without pillars must be a master workman!” Luther sheltered a hunted hare, and was shaken and saddened when hounds tore it to pieces.

“Biblia deutsch” . Übersetzt von Martin Luther (“The Bible” in German. Translated by Martin Luther) Lucas Cranach woodcuts. Wittenberg, 1534. It sold at the Leipzig Fair for two guilders, eight groschen for an unbound copy — comparable to half the salary of a schoolmaster. I have conscientiously translated the New Testament into German to the best of my ability. No one is forbidden to do it better. If someone does not wish to read it, he can let it lie. – On Translation – 1530 |

Working feverishly from Greek and Hebrew Scriptures, Luther translated the New Testament into a vigorous vernacular German in a scant 11 weeks. Like so much else about the man, it was a staggering achievement in its own right. By this feat, he singlehandedly created what was to become standardized High German (Hochdeutsch). At that time, the German language was divided into as many dialects as there were tribes and states; Saxons and Bavarians, Hanoverians and Swabians, could scarcely understand each other. Luther brought harmony out of this; borrowing liberally from such diverse sources as the poets, mystics, and trades, and he gave his language wings. His 1530 tract, “On Translating” is credited with laying the foundation of the modern science of linguistics, of Bible translation, and remains a classic of the German language. And, as usual, it flew in the face of Church law. In 1486, Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz (the same who had purchased his post at the expense of Saxony) had strictly forbidden the printing of sacred and learned books, giving as his reason that laymen and women could not understand Biblical subtleties and the German language was incapable of correctly rendering the profound sense of Greek and Latin works. Luther not only reformed his people’s faith, but their language, in creating a common classical tongue. When the New Testament was published, he set to work at once on the Old Testament. This appeared in installments until 1534, when the complete Bible was published by Hans Lufft. Luther’s Bible would run through an incredible 450 editions over the course of his lifetime. Still available, no German Bible has ever surpassed his for popular appeal.

When the ban against Luther was revoked, in February 1522, (his excommunication is unlikely to ever be lifted) he left his eagle’s nest and hurried back to a Wittenberg in the throes of anarchy. He immediately censured the peasants for looting and defiling the Churches, and, in the harshest terms, urged the princes to put down the insurrection. |

History has condemned him for “siding with the princes against the people,” but Luther’s lifelong message was of the triumph of the spirit and intellect over brute force, and this is surely why we remember him. “We must fight against the wolves, but on behalf of the sheep, not against the sheep.” A revolution is an essentially feral exercise — a pulling down and negation of what we despise, — and, as we have seen, Luther was no slouch when it came down to street fighting. However, the trick is in realizing a Reformation: the act of rebuilding and a return to founding principles demands courage, magnanimity, vision, and heart. It must be informed by love and decency, not hate. Luther was no Lenin — he would not revel in the mindless destruction of his adversary’s holy treasures. Neither would he seize them, as another old antagonist, King Henry VIII, would an estimated £1.3 million’s worth of Church property as his doctrine shifted with his fluctuating matrimonial fortunes.

..

..

Martin & Katharina, Lucas Cranach, 1528

Who loves not wine, woman and song, remains a fool his whole life long – Luther

In 1523, on Easter Sunday — emboldened by Luther’s message — Katharina von Bora and eleven other nuns who wanted to read Scripture, escaped from the Convent of Nimbschen near the town of Grimma. Disowned by their families, the young women found refuge in Wittenberg, with the family of Luther’s friend; the artist, Lucas Cranach the Elder. Feeling responsible for their irregular status — in such a society, young unattached women were hardly free agents — Luther took an interest in the plight of these girls. A letter dated August 6, 1524, confirms his deeply iconoclastic tendencies: “If friends and parents are unwilling to help, obtain help from other goodly people, regardless of whether your parents become angry, die or recover.” There is no indication that his interest was of a personal nature — at least, not at first. But after turning down several suitors, Katharina von Bora would accept Luther. They married on June 13th, 1525. Ironically, they set up married quarters in Luther’s old home — Wittenberg’s by-then-abandoned Augustinian monestary. By all accounts, theirs was a boisterously happy household, encompassing Martin, Katharina, their six children, Martin’s deceased sister’s six children, and Katherina’s  aunt Magdalena; while a permanent, but ever-changing cast of impoverished students, fugitives, and admirers of Dr.

aunt Magdalena; while a permanent, but ever-changing cast of impoverished students, fugitives, and admirers of Dr.

Luther ebbed and flowed among the family circle of fifteen. A contemporary sniffed: “A strangely mixed group of young people, students, young girls, widows, old women and children lives in the doctors house.” Katharina was reputed to be an excellent — if bossy — housekeeper, gardener, cattle breeder, and manager of a fish-pond. Luther boasted that his wife brewed the best beer in town. Family life would serve as the inspiration for the hundreds of Table Talk tracts (Tischreden) that Luther and his friends would produce. Luther preached at his church and taught at Wittenberg University until the end of his life; his last lecture ended with the words: “I am weak; I cannot go on.” Of their six children, just four survived childhood. All living descendants of Luther trace their lineage through his youngest daughter, Margarethe.

Go to sleep, dear little boy. I have no gold to leave you, but a rich God. If you become a lawyer, I will hang you on the gallows. Some lawyers are greedy and rob their clients blind, it is almost impossible for lawyers to be saved. It’s difficult enough for theologians. (Luther, to his son)

Go to sleep, dear little boy. I have no gold to leave you, but a rich God. If you become a lawyer, I will hang you on the gallows. Some lawyers are greedy and rob their clients blind, it is almost impossible for lawyers to be saved. It’s difficult enough for theologians. (Luther, to his son)

Shortly after celebrating his 62nd birthday, Luther was asked to settle a controversy between two bickering young nobles. He travelled through all the miseries of winter and fell ill in Eisleben, the town of his birth. In his final days, he nevertheless settled the dispute, preached four sermons, ordained two pastors, founded a school, wrote lighthearted letters to his worried wife and made notes for a new treatise. The world Luther departed was almost unrecognizable from that he had entered. It was no longer bounded by terrifying sea-monsters — Magellan had, at the cost of his own life, sketched out the bare bones of the  continents, and Gutenberg’s press would spread the liberating knowledge. Time itself was marked not by tolling church bells, but by the incessant ticking of innumerable clocks. The measure of the spiritual realm was less certain; Christendom was riven so fundamentally that Church reforms at the Council of Trent (1545-1563) could only ratify differences. The Peace of Augsburg granted freedom of worship to Protestants in 1555; yet, in the midst of this, Pope Paul IV (1555-59) said: “Even if my own father were a heretic, I would gather wood to burn him.” No better, was Luther’s own February 18, 1546, deathbed prayer: “I thank You for revealing to me Your dear Son, Jesus Christ, in whom I believe, whom I have preached and confessed, whom I have loved and praised, yet whom the shameful Pope and all the godless revile, persecute, and scorn.”

continents, and Gutenberg’s press would spread the liberating knowledge. Time itself was marked not by tolling church bells, but by the incessant ticking of innumerable clocks. The measure of the spiritual realm was less certain; Christendom was riven so fundamentally that Church reforms at the Council of Trent (1545-1563) could only ratify differences. The Peace of Augsburg granted freedom of worship to Protestants in 1555; yet, in the midst of this, Pope Paul IV (1555-59) said: “Even if my own father were a heretic, I would gather wood to burn him.” No better, was Luther’s own February 18, 1546, deathbed prayer: “I thank You for revealing to me Your dear Son, Jesus Christ, in whom I believe, whom I have preached and confessed, whom I have loved and praised, yet whom the shameful Pope and all the godless revile, persecute, and scorn.”

At his death, Europe would embark on a century and a half of ruinous religious warfare. On the other hand, Galileo, Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, Pieter Brueghel, Franz Hals, Rubens, Vermeer, Poussin, Bernini, Bronzino, El Greco, Manfredi, Murillo, Velázquez, Rembrandt, Napier, Elizabeth I, Ignatius Loyola, John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, J. S. Bach, Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Johnson, Miguel de Cervantes, Sir Philip Sidney, Samuel Pepys, John Milton, Montaigne, Edmund Spenser, Francis Bacon, Descartes — all were to be direct beneficiaries of Luther’s singular legacy; a climate of accelerated thought. Such prestige and recognition had the stubborn monk brought to his small German town, that Shakespeare made his Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, a student of Wittenberg University, and Christopher Marlowe made his Dr. Faustus, like Dr. Luther, a graduate of Wittenberg’s theological school.

People with ideas are our perpetual source of discomfort. We don’t really think of Luther much anymore and those who do, don’t really think much of him. His monumental achievements are forever subordinate to “what he did to the Church,” “what he said about the Jews,” or “his insensitivity to women.” As Luther might have been the first to ask: isn’t imposition of our (dubious) moral authority on persons 500-years-dead something of an arrogance in itself? Alas, it has always been fashionable to dismiss Luther as not quite relevant or not quite nice. All his life he was accused of the oldest (and surprisingly contemporary) Christian libel — odium humani generis — hater of the human race: used to such cruel effect in devising tortures against the early Christians. As if to punish the man who did not even want the new Church named after him, Luther was omitted from official histories over 45 years of Communist rule in East Germany. During those dark years, Wittenberg’s sole claim to egalitarian glory was a poisonous chemical industry. Today, Luther is eclipsed by the ubiquitous presence of an American civil rights activist. It is ironic in the extreme to remember that Martin Luther King (born just, plain, Michael King) legally changed his name in tribute to a man he rightly regarded as absolutely without peer.

Man is a better creature than heaven and earth and all that is between them. Lecture on Genesis – 1535

Man is a better creature than heaven and earth and all that is between them. Lecture on Genesis – 1535

NOTE

The Luther Rose (see left) was Luther’s personal seal. He designed it with these elements in mind: as one believes with the heart, the cross is superimposed on the heart. Faith brings comfort, purity and peace, as represented by the white rose. Belief and faith bring the promise of heaven, in the blue field behind the rose. A gold ring signifies that “heaven endures forever and ever and is more precious than all pleasures and posessions of earth, as gold is the most precious and the noblest metal.”

The Luther Rose (see left) was Luther’s personal seal. He designed it with these elements in mind: as one believes with the heart, the cross is superimposed on the heart. Faith brings comfort, purity and peace, as represented by the white rose. Belief and faith bring the promise of heaven, in the blue field behind the rose. A gold ring signifies that “heaven endures forever and ever and is more precious than all pleasures and posessions of earth, as gold is the most precious and the noblest metal.”

LINKS

Disputation of Martin Luther (the 95 theses)

Luther on changelings and killcrops

Changing politics and changing interpretations of Luther

Rules on Prohibited Books: only the titles change

The usually excellent Catholic Encyclopaedia’s surprisingly tendentious “Luther” entry

Interesting: The Dance of Death & examples from European churches

German monk’s encryption mystery – three people “got it” in 500 years

Janissaries – captive Christians in the Ottoman Empire

Making of a Janissary (The Turkish Education Association)

Shock troop slaves – the sultan’s Janissaries