Then and Now: People Really Do Get the Leaders They Deserve

My booklet, Harry Stevens, was conceived in a somewhat convoluted fashion. In the spring of 1989, the seventy-fifth anniversary of the “Komagata Maru” incident approached, engendering a gnashing of teeth and a rending of garments on the part of the provincial and federal politicians, academics, minority toadies and multiculturalists of every stripe. Paul Fromm asked me to collect some information on William Hopkinson, a superintendent of immigration murdered in Vancouver by a Sikh terrorist at the conclusion of the incident.

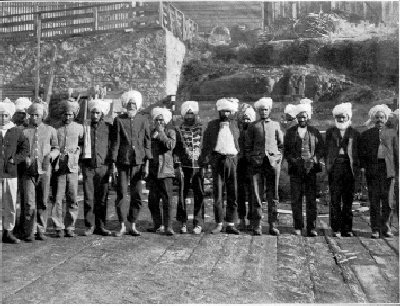

One of the first Sikh groups to arrive in Vancouver, 1906

In the course of my investigation, carried out for the most part in the Vancouver Public Library and in the Vancouver City Archives, I discovered that during the years 1905 to 1907, something like a full-fledged invasion from China, India and Japan to British Columbia occurred. In response to this invasion, the Asiatic Exclusion League was formed in Vancouver on July 24, 1907, and was affiliated with similar organizations in Seattle, Portland, San Francisco and other Pacific coast cities.[(Jarvis, Robert The Workingman’s Revolt: The Vancouver Asiatic Exclusion Rally of 1907 Citizens for Foreign Aid Reform Inc. Toronto, Ontario, 1991.)]

At 11 a.m. on May 22, 1914, pilot Barney Johnson, achored the steamship “Komagata Maru” off number 2 berth in Vancouver harbour. On board were 376 illegal East Indian immigrants, most of them Sikhs from the Punjab. One month later, a protest meeting was called by Vancouver’s mayor Baxter, to be held at Dominion Hall.

What transpired was one of the most significant speeches made by a Canadian politician in the early part of this century. Stevens was the first speaker. “Very simply,” he explained, “what we face in British Columbia is this – whether or not the civilization which finds its highest exemplification in the Anglo-Saxon British rule, shall or shall not prevail in the Dominion of Canada. … I have no ill-feeling against people coming from Asia personally, but I reaffirm that the national life of Canada will not permit any large degree of immigration from Asia. … I intend to stand up absolutely on all occasions on this one great principle – of a white country and a white British Columbia.” This statement was followed by thunderous applause.

Henry Herbert Stevens was born on December 8, 1878 in Bristol, England. Nine years later, young Harry, his widowed father and three siblings immigrated to Canada; first to Ontario, and later to Vernon, British Columbia. In Vernon, Stevens started his working life, first as a grocery clerk, and later as a fireman for the C.P.R. and as a stagecoach driver.

Early in 1900, he went to the Philippines, and later as a civilian volunteer attached to the American forces, he served in China during the Boxer Rebellion. To Stevens, China was a foreign and crowded country, whose emigrating citizens could undermine the British heritage that was the bedrock of society in British Columbia.

Victoria’s ramshackle Chinatown 1886

Stevens returned to the Vancouver area in 1901, and a year later went to work as a miner near Nelson, B.C. He joined the Western Federation of Miners, and soon became secretary of the local union, using his free time to read Karl Marx, K.S. Mill and Fredrich Engels. He joined the Conservative Party and became active in the Methodist Church, the Sons of England, the Orange Lodge, and the Termial City Club. He later married and fathered five children.

During these years Stevens entered electoral politics in the civil contest of 1910, winning a place on the City Council for Ward 5 (Mount Pleasant), where he lived. Returned the following January, he then surprised political observers by winning the Conservative nomination for Vancouver City Centre in the Federal election of 1911.

Stevens saw himself as an ordinary man representing ordinary people. His family background, his Methodism, his occupations as grocery clerk, bookkeeper, and real estate agent rooted him solidly in the middling strata of society. Furthermore, his 1898-99 season spent mining at Phoenix, British Columbia, had introduced him to trade unions, and to the economic plight of wage earners.

Then, as now, thoughtful people could hardly help but notice that Canada had pressing social problems of its own – Child in a Toronto slum, 1913

Harry Stevens was perhaps the most outspoken critic of Oriental, and later “Hindu” immigration. In March 1914, he opined: “I find that civilization finds its best exemplification in the civilization which we see in the British Empire and in other countries of Northern Europe. I hold that it is a sacred trust of the Anglo-Saxon and kindred peoples to hold that civilization and to cherish it. … We cannot hope to preserve the national type if we allow Asiatics to enter Canada in any numbers.”

When the first Sikh died in Vancouver (1907), the body was spirited away in the dead of night and taken to its pyre – Not an action calculated to endear God-fearing Vancouverites –

The arrival of the “Komagata Maru” in Vancouver produced a storm of protest throughout British Columbia.

On the morning of June 24, 1914 a serious development in the proceedings surrounding the “Komagata Maru” was reported from Ottawa. The government intended to let the Hindus land and to test their right of entry in the courts. A thoroughly alarmed H.H. Stevens declared that he “… opposed any such move to the limit. The landing of these Hindus would be much more likely to cause riots, than keeping them where they are.”

It was decided that police and immigration forces would take possession of the ship, while local militia would remain on the wharf to await emergencies. The tug “Sea Lion” with 125 Vancouver city policemen and thirty-three special immigration police aboard reached the “Komagata Maru” at one o’clock on the morning of the 19th. The attacking force, acting with determination and courage, was met with a fusilade of coals, bricks and scrap iron. One Sikh, Herna Singh, possessed a revolver, and opened fire on Harry Stevens and William Hopkinson, a Canadian government inmmigration inspector; fortunately without effect. Fifteen minutes after the beginning of the battle, the “Sea Lion” backed away from the steamer’s side and retuned to the pier. The East Indians yelled more loudly than ever and promised “… to cut the hearts out of any dogs of the white race who came aboard the ‘Komagata’.”

The Komagata Maru swings at anchor as dozens of small pleasure craft go out to see the source of this curious behaviour for themselves

The police had attempted to take possession of the “Komagata Maru”, and had failed. But there was one man who saw the picture with absolute clarity: Harry Stevens. The solution to the problem was the H.M.C.S. “Rainbow”.

Immediately, steps were taken to put the “Rainbow”, an elderly training cruiser, into operational condition. By July 20 she was ready and on the morning of the 21st she slipped quietly into Burrard Inlet and anchored near the “Komagata Maru”.

Passengers on board the Komagata Maru

Meanwhile, Commander Walter Hose of the “Rainbow” ordered his crewmen to strip the tarpaulins off the ship’s guns as a show of force. An estimated 30,000 citizens left their jobs and households to flock to rooftops, fire escapes and windows affording clear views of the harbour spectacle.

On the morning of July 23, 1914, the “Komagata Maru” left her anchorage in Burrard Inlet. Five days later, Austria declared war on Serbia, and Canada, along with the rest of the British Empire, was at war.

At the same time, plans were being made for the assassination of William Hopkinson; and at 10:15 on October 21, 1914, Hopkinson was shot to death at the provincial courthouse by one Mewa Singh. [ For more information on Hopkinson and the “Komagata Maru”, see: The “Komagata Maru” Incident: A Canadian Immigration Battle Revisited, Citizens for Foreign Aid Reform Inc, Toronto, Ontario, 1992]

When war broke out in August, Harry Stevens had immediately tried to enlist, at the age of 36.

Mounted Canadian troops head to Vimy Ridge 1917

He was told that he could contribute more on the home front, and for the most part, Harry Stevens’ role during the First World War was that of a hard-working parliamentary back bencher.

Ten years of loyal work were rewarded when Stevens was named to the Cabinet, before the election of 1921; assuming the Trade and Commerce portfolio. He was recognized, even by the opposition press, as a good cabinet acquisition. Indeed, the Winnipeg Free Press ranked him as the best of the new group, almost ignoring another new minister, R.B. Bennett. By the time the election of 1925 rolled around, Stevens had become a major Tory spokesman, campaigning throughout the country.

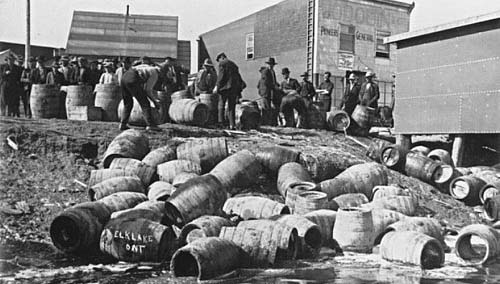

Alarmed by the two-way smuggling of alcoholic beverages hard pressed Canadian merchants set up a special organization of their own to investigate the liason between venal customs enforcement agents and smugglers.

Bootlegger’s kegs destroyed in Ontario early 1920s

The embattled merchants turned to one of their own: Harry Stevens. The immediate result was the setting up of a nine-man parliamentary committee to investigate the Customs Department. Although the hearings were dominated by Stevens, R.B. Bennett was nevertheless exceedingly active in questioning the witnesses and drafting the final, unanimous report.

Disturbed by what Stevens regarded as the taking over of the Conservative Party by a few wealthy individuals, and feeling the need of looking after his neglected business interests in Vancouver, Stephens submitted his resignation to the House on 31 October, 1929. R.B. Bennett, now leader of the Conservative opposition, finally persuaded Stevens to withdraw his resignation.

By that time, Canada, as well as the rest of the world, was in the throes of the Great Depression.

The Alberta Dustbowl – Alberta Provincial Archives

In December, Bennett, now Prime Minister, decided to break a year-long self-imposed moratorium on public speeches; and decided to address the economic situation.

In January 1935, Prime Minister Bennett, influenced by his brother-in-law, W.D. Herrige, who had been greatly influenced by Roosevelt’s New Deal, made the first of his five “New Deal” broadcasts which fell upon the unsuspecting public and his dismayed cabinet.

Although steadfastly loyal to the Conservative Party during his quarter century as an M.P. for Vancouver, Harry Stevens resented the influence that big businessmen enjoyed within it. The Depression had made what Stevens referred to as “unfair or unethical trading practices.” Stevens used Canada Packers as one of his illustrations but the blackest villians, in his view, were the major department stores. The capitalist system, in his opinion, had not failed: a few big capitalists had failed the system. “Decent businessmen” were urged to help him correct the abuses and to “save the civilization we are proud to call Canadian.”

The beginning of the end to Steven’s career as an orthodox Tory had arrived.

On Dominion Day, July 1, 1935, a riot broke out in Regina’s market square, during a march of the unemployed to Ottawa. A policeman and a marcher died, many were injured and scores were arrested before the RCMP and city police restored order.

Whatever Bennett might do to try to alleviate the depression, Stevens thought the result would be “the ruination of the party. I do not think the Conservatives under his leadership has the remotest chance for success in the coming election.” Stevens admitted that “there was a very strong demand for me to lead a third party.” On July 5, as Parliament was winding up its business, thirty-one people meeting in Hamilton signed a petition. It requested that H.H. Stevens form a new party: “to reestablish Canada’s industrial, economic and social life to the benefit of the great majority.” The next day Harry Stevens made known his decision: he would lead a new Reconstruction Party, dedicated “to the plight of youth.” An accompanying statement from Warren K. Cook, the new party’s chairman and secretary, said that his recent nation-wide tour indicated that the party would have strong support, especially in Quebec.

The Regina riot was not repeated, but it served as a dismal valedictory to Bennett’s five year fight against the depression. On June 20, he announced the he would remain as Conservative leader and lead his party in a general election.

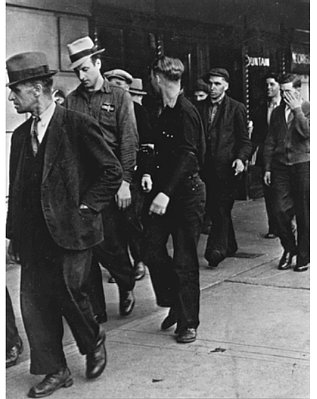

Unemployed in Ontario – early 1930s

No leading Conservatives joined Stevens, but many leading Tories declined to re-offer. In Quebec, the former provincial organizer of the 1930 campaign, Jacques Cartier, resigned his post as vice-chairman of the Radio Commission to become provincial organizer for the Reconstruction Party. By the time nominations had closed for the October 14 general election, there were 174 Reconstruction candidates, most of them political novices, with 33 farmers forming the largest single group.

After the founding of the new party, in reply to a backbencher who urged him to make known the fact that “he had not bolted” from the Conservatives , Stevens placed some of the blame for his lack of support by Tory backbenchers on the spinelessness of the Conservative M.P.s: “[Bennett’s] action was one of pique and personal pettiness… [but] private members of the Conservative Party have been very derelict in their duty… in not long ago resisting the dominaring attitude of their leader. They will talk, as most of them did, very freely behind his back, but for some reaon or other, with few exceptions, were afraid to express their views to his face. Had they done so things could have been very much different today.”

There were no monthly Gallup polls to chart the government’s terminal condition, but its symptoms were manifest. In provincial elections in June and July the last two Tory governments fell by astonishing margins: only eight Conservatives were returned to New Brunswick’s forty-eight constituencies, and on Prince Edward Island the Liberals carried every seat.

Steven’s schism won many rank-and-file Conservatives, notably in Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia. No M.P.’s bolted to the new party, but many incumbents refused to seek renomination. Led by E.N. Rhodes and a half-dozen othe ministers, nervous Conservatives sought shelter from the gathering electoral storm in the Senate, on the bench, or on a government-appointed board.

An air of excitement hung over the large conference room of the Royal York Hotel on the evening of 11 July when Harry Stevens spoke to the press. He and the executive of the Reconstruction Party were drafting a manifesto “to grapple the pressing problems with the purpose of improving the conditions of the masses.”

Fifteen points summarized the “New National Policy of Reconstruction and Reform”; a pledge to youth, a system of public works, including the completion of the Trans-Canada Highway, a national housing program; and in order to balance the budget, a Reconstruction government would administer federal taxes “through a single set of auditors” and would invite the provinces to cooperate in the system which would divide the returns on “an equitable and agreeable basis.” The Tory raft was breaking up. In the riding of Simcoe East, W.M. Cramp resigned as president of the local Conservative Club to become a Stevens supporter and later, the third Reconstructionist to be nominated. In the riding of London, the Conservative incumbent, Frank White, was not renominated by his party, apparently because of his outspoken support of Stevens. In Leamington, the Young Canada Conservatives Club was formally dissolved, and every member but one promptly joined a “Stevens Club”. In the end, only eight members of the original Bennett cabinet were on hand to help him fight the election. Four would be successful in their constituencies.

For his part, Bennett rarely referred to Stevens in his speeches, except to describe his policies as demonstrably unsound and to deplore his attempt to divide the forces of progress.

R.B. Bennett in his “Windsor” uniform

Besides the candidates put forward by the old-line parties, there were 174 Reconstructionists, 118 CCFers and 45 Social Creditors, emboldened by their success in Alberta. Eighty-one other candidates joined the field, including 11 Communists and a Technocrat. The bewildering array of aspirants for the October 14 balloting totalled 894,363 more than 1930; and reflected the ideological turbulence of the mid-thirties.

The Reconstruction Party was largely an act of political desperation; it had no ideological base to compare with that of the CCF, Canada’s socialist party, or even the Social Credit Party. It was led by a dissident Tory, who, somewhat late in his career, had championed the cause of the hard-pressed producers, small business owners, and thousands of nameless Canadians caught by the depression. The party had no long-range planother than to force through enough broad legislation to protect the little man.

For W.L. Mackenzie King, head of the Liberal Party, and leader of H.M. opposition the campaign was easy. He only have to await the certain end of the Government, to summon that ever reliable witness, hard times, to denounce all Bennett’s remedies, though he had few of his own, to say that Bennett’s “New Deal” was composed either of illegal measures, of reforms stolen from Liberal policy or of some dangerous “fascist” schemes like a private central bank. His ally, the depression, would do the rest.

The Liberal “policy of having no policy” produced a parliamentary majority that astounded the pundits: 173 of the 245, the most one-sided election since Confederation.

No party had ever before won such an overwhelming victory. The Liberals won twenty-five of the twenty-six seats in the Maritimes, and sixty of the sixty-five in Quebec. Even in Ontario they carried fifty-six out of eighty-two, the largest Liberal representation in sixty years. Manitoba and Saskatchewan together returned thirty Liberals from thirty-six constituencies. Only in the far west were the results disappointing. One Liberal was elected out of seventeen ridings in Alberta and six from sixteen in British Columbia. The Social Credit Party elected fifteen in Alberta and two in adjoining constituencies in Saskatchewan. The CCF, with 119 candidates, alected seven, all in the west. Stevens was now truly a one-man party, out of 174 candidates, he would be the only Reconstructionist member in the House. For the Conservatives it ewas a rout. Forty members were returned, twenty-five from Ontario, five from Quebec, five from British Columbia, one each from the other five provinces, and none from Nova Scotia or Prince Edward Island. Rwelve of the eighteen Cabinet ministers were defeated. It was the smallest Conservative contingent in the House of Commons since Confederation.

For Bennett and the Conservative Party, the decision was devastating, in terms of votes cast and seats lost. It was a heavy poll, with 75 per cent of those eligible voting. The Liberal vote was 2,076,394, the Conservatives 1,308,688, and that for the Reconstruction Party 389,708; while the CCF and the Social Credit parties garnered 386,484 and 187,045 votes respectively.

Bennett had a presentiment that he was facing defeat, and he had no doubts concerning the reason. When he was in Calgary during the campaign, he went into the dining room of the Palliser Hotel and saw an old friend, Frank Holliway. Holliway asked Bennett how he considered the campaign was going. Bennett replied: “I wouldn’t say this to anyone else, Frank, but I think we’ve lost. And one man has crucified the Party: Stevens.”

No one can ever hope to calculate what the rift between Bennett and Stevens cost the party in terms of its disaster on polling day, but it is possible to make some estimate of how many seats the votes cast for the Reconstruction Party cost the Conservative candidate his victory; and the results are startling.

The Reconstruction Party made a small showing in most of Quebec, British Columbia and Nova Scotia, and it had avoided the prairies. Its greatest strength proved to be in Central Canada, in ridings directly concerned in trade and industry. In these, on election day, the balance between Liberal and Conservative voters was almost even, and it was very frequently the intervention of a Reconstruction candidate that turned the scale; generally against the Conservatives. In no fewer than forty-eight ridings the combined total of the Conservative and Reconstruction vote would have been sufficient to have defeated the Liberal candidate.

For Harry Stevens and his Reconstruction Party the election was an unqualified disaster. They attracted the support of the Canadian Retail Merchant Association and other small business groups, but only in Nova Scotia were they able to broaden their base to include working-class elements. In addition to its other difficulties, the party entered the election with a war-chest of only $35,000, a pitifully small amount of money for a national election, even by 1930s standards.

Reconstructionists recieved 8.7% of the popular vote, but it was spread so thinly across the country that only Stevens was able to win a seat.

In 1940, the Conservatives were a weak and poorly led opposition, and they were no stronger two years later when they gathered once again in Winnipeg to choose a leader. Arthur Meighen had convinced many delegates that John Bracken, the Manitoba Progressive premier was the logical choice, but when M.A. MacPherson decided to try again, others followed suit. First, John Diefenbaker and then Howard Green entered their names. Finally, so did Harry Stevens. According to R.D. Finlayson, who had helped to organize the convention: “Stevens made the only good speech.” After it ended, Finlayson’s companion turned to him and lamented: “Oh, what a pity! There was our leader.”

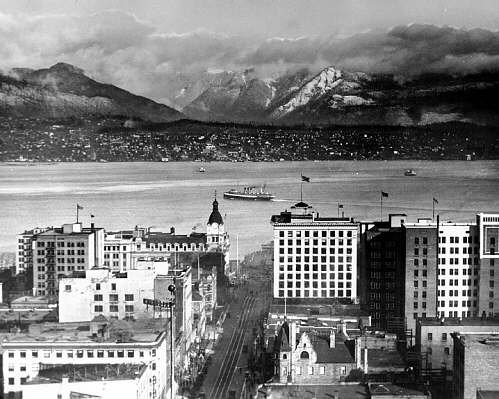

Central Vancouver in the 1920s

It was the last time that Harry Stevens challenged the inner circle of the Conservative Party. He did not enter the 1945 general election, but ran again in Vancouver Centre in 1949 and again in 1953. It was to no avail; his political career was over. In 1948, he sent John Diefenbaker a five-page memo to assist him at a speech at the Conservative convention. In 1949, George Marler, a CPR vice-president, asked him to draft a new labour code for Canada, a request which implied a certain regard for him among the conventional business community.

Stevens represented Vancouver in Parliament for nineteen years and the constituency of Kootenay East for another ten, he was retired f rom electoral office in 1940.

Stevens continued to live in Vancouver until his death on 14 June 1973. He remained a hard core British and Canadian patriot; and an Asiatic exclusionist to the end.

Robert Jarvis