Every honest boozer, every decent gouty gentleman, everyone who is dry, may come to this barrel of mine. Rabelais (Gargantua and Pantagruel – 1532) There are persons living today who remember Canada “Before Enrichment”. Well, living may be too strong a word for it. If you were educated within the last thirty years, you certainly know that early Canadian history is presented in a way that is not merely dull, but dull to the point of interfering with normal brain function. Still, let’s give schools some credit. They at least concede that there was a pre-multicultural Canada. As if 1967, rather than 1867 marked confederation, our government takes every opportunity to insist that “Canada has no history — has no culture”. It’s a shame really, because this leads us irresistably to think of the early Europeans (if we have to think of them at all) as sour, little one-dimensional figures, excessively intolerant and zealously religious — that is, when they weren’t actively bashing an aboriginal head in. When we think of Cabot, Cartier, or Champlain’s men attaining this continent, we envision a collection of old coots wading ashore, and collapsing to their knees to recite interminable prayers of thanksgiving. Well, we’re here to tell you, that they probably fell. More than likely the first words uttered on achieving the New World were (time and time again): “Hey, what happened to that bottle?”

Every honest boozer, every decent gouty gentleman, everyone who is dry, may come to this barrel of mine. Rabelais (Gargantua and Pantagruel – 1532) There are persons living today who remember Canada “Before Enrichment”. Well, living may be too strong a word for it. If you were educated within the last thirty years, you certainly know that early Canadian history is presented in a way that is not merely dull, but dull to the point of interfering with normal brain function. Still, let’s give schools some credit. They at least concede that there was a pre-multicultural Canada. As if 1967, rather than 1867 marked confederation, our government takes every opportunity to insist that “Canada has no history — has no culture”. It’s a shame really, because this leads us irresistably to think of the early Europeans (if we have to think of them at all) as sour, little one-dimensional figures, excessively intolerant and zealously religious — that is, when they weren’t actively bashing an aboriginal head in. When we think of Cabot, Cartier, or Champlain’s men attaining this continent, we envision a collection of old coots wading ashore, and collapsing to their knees to recite interminable prayers of thanksgiving. Well, we’re here to tell you, that they probably fell. More than likely the first words uttered on achieving the New World were (time and time again): “Hey, what happened to that bottle?”  The Embarkation of the Pilgrims,Robert W.Weir 1843 Rotunda of the US capital A ship’s manifest of 1630 shows that the Puritans (of all people) had thoughtfully provisioned themselves with 10,000 gallons of beer, 120 hogsheads of brewing malt, and a dozen gallons of distilled spirits. No wonder construction of a stockade was generally the first order of business. “In the late seventeenth century the Rev. Increase Mather [father of Cotton, the man who would preside over the 1692 Salem witch hysteria] had taught that drink was ‘a good creature of God’ and that a man should partake of God’s gift without wasting or abusing it. His only admonition was that a man must not ‘drink a Cup of Wine more than is good for him’. … At that time inebriation was not associated with violence or crime; only rowdy, belligerent inebriation in public places was frowned upon.” (1)

The Embarkation of the Pilgrims,Robert W.Weir 1843 Rotunda of the US capital A ship’s manifest of 1630 shows that the Puritans (of all people) had thoughtfully provisioned themselves with 10,000 gallons of beer, 120 hogsheads of brewing malt, and a dozen gallons of distilled spirits. No wonder construction of a stockade was generally the first order of business. “In the late seventeenth century the Rev. Increase Mather [father of Cotton, the man who would preside over the 1692 Salem witch hysteria] had taught that drink was ‘a good creature of God’ and that a man should partake of God’s gift without wasting or abusing it. His only admonition was that a man must not ‘drink a Cup of Wine more than is good for him’. … At that time inebriation was not associated with violence or crime; only rowdy, belligerent inebriation in public places was frowned upon.” (1)

- “Thou dost cause grass to grow for the cattle and plants for man to cultivate, that he may bring forth food from the earth, and wine to gladden the heart of man.” 104th Psalm

Fifteen years before the Pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower, Samuel de Champlain founded North America’s first Epicurean social club in Acadia. “We spent this winter [1606-07] very pleasantly, and had good fare by means of the Order of Good Cheer which I established, and which everybody found beneficial to his health, and more profitable than all sorts of medicine we might have used. This Order consisted of a chain which we used to place with certain little ceremonies about the neck of one of our people, commissioning him for that day to go hunting. The next day it was conferred upon another, and so on in order. All vied with each other to see who could do the best, and bring back the finest game. We did not come off badly, nor did the Indians who were with us” (2) The recipient of the Order of Good Cheer (or rather, Ordre du Bon Temps) was also expected to organize the evening’s entertainment. “And at night, before giving thanks to God, he handed over to his successor in the charge the collar of the Order, with a cup of wine, and they drank to each other.” (Lescarbot, History of New France, 1617) Given the fact that thirty-six of the seventy-nine man complement had died of scurvy the previous year, Champlain’s innovation was a happy inspiration. Beneathe the dancing, tapping feet, 45 butts (108 Imperial gallons each) of lustrous red and white Bordeaux wines waited in Port Royal’s newly constructed cellars. Bordeaux is justly reckoned an excellent “keeping” wine, but not this batch. Over the course of that winter, Champlain’s men consumed more than 250 litres apiece.

Champlain and the Order of Good Cheer An archeological dig at the 1624 Quebec settlement shows that these early residents were not just determined, but sophisticated bon vivants. “Chantepleures” (or brass barrel taps) have been unearthed along with what was still a rarity in the early 17th century — fine glass wine goblets. Rhenish wine jugs (decorated with a bearded mask) have also been recovered, indicating that those fine Bordeaux were chased with Rhine wines. Recounting an exceptionally cold winter, Champlain laments: “All our liquors froze, except the Spanish wine. Cider was dispensed by the pound [like popsicles].” (The Voyages) The drinking and rowdy behaviour of the voyageurs and coureurs des bois soon provoked a general alarm and the king of France was informed that, thanks to them, New France was about to revert to a wild state. An anonymous memoir dated from 1705 complains, “the existence of the coureurs des bois is a perpetual state of idleness that leads them to all manner of disorderliness. They sleep, smoke, and drink alcohol, regardless of the cost. … They are totally independent and accountable to no one; they recognize no superior, judge, law or police, and they refuse to subordinate.” Worst of all, they did not marry or cultivate the land.

…

…

Portage, John Innes | Warping the fur barge, John Innes Warping the Fur Barge Upstream – John Innes The Museum of New France has estimated that as each voyageur’s canoe set out, it was awash with an average 100 to 125 litres of spiritous liquors, “reserved for the travellers and the Frenchmen who stayed at the trading posts”. In colonial America, “parents gave it [alcohol] to children for many of the minor ills of childhood, and its wholesomeness for those in health, it appeared, was only surpassed by its healing properties in case of disease. No other element seemed capable of satisfying so many human needs. It contributed to the success of any festive occasion and inspirited those in sorrow and distress. It gave courage to the soldier, endurance to the traveller, foresight to the statesman, and inspiration to the preacher.. It sustained the sailor and the plowman, the trader and the trapper. By it were lighted the fires of revelry and of devotion. Few doubted that it was a great boon to mankind.” (3)  “White males were taught to drink as children, even as babies. ‘I have frequently seen Fathers,’ wrote one traveller, ‘wake their Child of a year old from a sound sleap [sic] to make it drink Rum, or Brandy.’ As soon as a toddler was old enough to drink from a cup, he was coaxed to consume the sugary residue at the bottom of an adult’s nearly empty glass of spirits. Many parents intended this early exposure to alcohol to accustom their offspring to the taste of liquor, to encourage them to accept the idea of drinking small amounts, and thus to protect them from becoming drunkards” (4) — a precaution that appears to have been lost on successive generations of Canadians.

“White males were taught to drink as children, even as babies. ‘I have frequently seen Fathers,’ wrote one traveller, ‘wake their Child of a year old from a sound sleap [sic] to make it drink Rum, or Brandy.’ As soon as a toddler was old enough to drink from a cup, he was coaxed to consume the sugary residue at the bottom of an adult’s nearly empty glass of spirits. Many parents intended this early exposure to alcohol to accustom their offspring to the taste of liquor, to encourage them to accept the idea of drinking small amounts, and thus to protect them from becoming drunkards” (4) — a precaution that appears to have been lost on successive generations of Canadians.

Rules of Civility – penmanship exercise attributed to 12-year-old George Washington Unlike Canadians, Americans have taken exquisite pains to preserve their legacy of patriot rebels, revenuers and  moonshiners. Emphasis on the latter may have inadvertantly contributed to the misapprehension that they were in any sense, world-class drinkers. American schoolchildren are taught that George Washington, the “Father of the country”, couldn’t lie – ours could hardly stand. Sir John A. Macdonald was an inspired speaker, a vigorous fighter, and a frequent tippler. His interminable feud with dour, teetotaling Liberal political rival George Brown, caused him to quip: “The nation prefers John A. Macdonald drunk to George Brown sober.” Once, when he was called on to speak in a close meeting hall, he rose unsteadily to his feet and promptly threw up. When the mess was cleaned up, he returned to centre stage and apologized. Then he pointed to George Brown and said, “I couldn’t help it, that man always makes me sick.” “For God’s sake – not in the sink!” – coping with the Canadian houseguest Our archival failings may not be so much a case of indifference, as a genuine inability to remember what happened the year (or night) before. It’s safe to assume that if America did manage to produce any formidable drinkers, they came by way of Canada. Certainly, early reports from American visitors dwell on the quality and quantity of Canada’s two-fisted drinking habits. In 1823, “Gentlemen in Canada appear to be much addicted to drinking. Card-playing, and horse-racing are their principal amusements. In the country parts of the province [Ontario], they are in the habit of assembling in parties at the taverns, where they gamble pretty highly, and drink very immoderately, seldom returning home without being completely intoxicated. They are very partial to Jamaica spirits, brandy, shrub, and Peppermint; and do not often use wine or punch. Grog, [watered down rum] and the unadulterated aqua vitae, are their common drink; and of these they freely partake at all hours of the day and night.” (5) An Englishman visiting in 1876 helpfully opines: “I believe that one reason why Canadians are a healthier and more robust race than the Yankees is that they drink better liquor.” (6)

moonshiners. Emphasis on the latter may have inadvertantly contributed to the misapprehension that they were in any sense, world-class drinkers. American schoolchildren are taught that George Washington, the “Father of the country”, couldn’t lie – ours could hardly stand. Sir John A. Macdonald was an inspired speaker, a vigorous fighter, and a frequent tippler. His interminable feud with dour, teetotaling Liberal political rival George Brown, caused him to quip: “The nation prefers John A. Macdonald drunk to George Brown sober.” Once, when he was called on to speak in a close meeting hall, he rose unsteadily to his feet and promptly threw up. When the mess was cleaned up, he returned to centre stage and apologized. Then he pointed to George Brown and said, “I couldn’t help it, that man always makes me sick.” “For God’s sake – not in the sink!” – coping with the Canadian houseguest Our archival failings may not be so much a case of indifference, as a genuine inability to remember what happened the year (or night) before. It’s safe to assume that if America did manage to produce any formidable drinkers, they came by way of Canada. Certainly, early reports from American visitors dwell on the quality and quantity of Canada’s two-fisted drinking habits. In 1823, “Gentlemen in Canada appear to be much addicted to drinking. Card-playing, and horse-racing are their principal amusements. In the country parts of the province [Ontario], they are in the habit of assembling in parties at the taverns, where they gamble pretty highly, and drink very immoderately, seldom returning home without being completely intoxicated. They are very partial to Jamaica spirits, brandy, shrub, and Peppermint; and do not often use wine or punch. Grog, [watered down rum] and the unadulterated aqua vitae, are their common drink; and of these they freely partake at all hours of the day and night.” (5) An Englishman visiting in 1876 helpfully opines: “I believe that one reason why Canadians are a healthier and more robust race than the Yankees is that they drink better liquor.” (6) “See the embarrassment and reproach in the fruitless waste that is drinking. If you ever go away drunk and fall asleep on the road, then you’ll never make it home, and you will pay dearly for it. They’ll steal all your clothes from you. And if you do not regain your sobriety, you will lose both your body and your soul, for many drunkards have perished from wine and frozen to death along the roadside.” Domostroi, chapter 15 – a 16th-century guide to living by Ivan the Terrible’s spiritual mentor, Father Silvester Like a 120 proof puddle slowly spreading across the country, inebriation appears to have been the unavoidable consequence of Canadian settlement. In the Montreal of 1754, “despite the frequent tavern brawls and duels, the incidence of crimes of violence was not great. … Evidence that the Canadians were anything but subservient to clerical authority is provided by the frequent ordonnances of the intendent ordering the habitants of this or that parish to behave with more respect toward the cloth; to cease their practice of walking out of church as soon as the curé began his sermon; of standing in the lobby arguing, even brawling, during the service; of slipping out to a nearby tavern; of bringing their dogs into church and expostulating with the beadle who tried to chase them out.

Frequently the bishop thundered from the pulpit against the women who attended mass wearing elaborate coiffures and low-cut gowns.” (7) Here, at least, we have an insight into Quebec’s mighty fecundity. In Nova Scotia, “despite the sparse population of the province in 1760, Halifax already boasted over 100 grog shops. … At one dinner for military gentlemen, exactly 120 bottles of wine were consumed by forty-seven diners, and they topped that with half a bottle of brandy per man. … At another memorable party, the gentlemen drank twenty-eight bumper toasts; that is, at each toast the whole glass had to be emptied, standing. Almost everyone drank too much. Rum from the molasses of the Caribbean was so cheap that tradesmen set out a barrel of it, complete with tin cup, so that customers could help themselves. Most households had a barrel in the cellar. Two Halifax distilleries turned out ninety thousand gallons a year. A new settler writing home said of Halifax that the business of half the town was selling rum and of the other half, drinking it.” (8)

- ‘Here’s a bumper, brave boys, to the health of our king, Long may he live, and long may we sing!” Loyalist song – 1779

Here’s a more familiar tune- “You’ll think as you’re told to think” Tarring and feathering a Loyalist Dipsomaniacal pathology only grew more pronounced as Canadians moved farther away from Mother Europe. At British Columbia’s Fort Victoria, the Hudson’s Bay Company had to contend with thirsts of truly Bunyanesque proportions. Thank heaven for prim Robert Melrose. His most enduring contribution is a meticulously detailed chronicle of his lampshade-wearing neighbours’ many shortcomings (circa 1850). Inadvertantly, he may have contributed one of the earliest studies of disinhibition vs. motor impairment. His certainly wasn’t a course of action calculated to endear him to a town teeming with violently rowdy roughnecks. “The Bacchanalian sons of Vancouver Island, have, at length excited my curiosity so far, that I am determined for the future, to register their names according to their prowess. … New Year’s Day, a day above all days for rioting in drunkenness. … The grog shops were drained of every sort of liquor, not a drop to be got for either love or money. … It would have taken a line of packet ships, running regular between here, and San Fransisco to supply this island with grog, so great a thirst prevails amongst its inhabitants.” (9) If anything, Melrose was over generous. John Helmcken, (son-in-law to Governor Sir James Douglas) describes a pathetic alcohol-fueled scene of pandemonium among the HBC labourers: “On one occasion the men were all intoxicated.

Mr. Douglas gave orders to search for the liquor: after much trouble a barrelful was found hidden under the floor of the men’s house. The men would defend it so we all had to go, the parson with a long sword that had belonged to one of his celebrated ancestors, who had been hung for something against the state. The men were all forced to our end of the room, whilst we got out the whiskey. Staines stood with his sword stretched out across the room and called ‘Pass this who dare!’ … The barrel was taken out into the Fort Yard and Mr. Douglas said. ‘ Knock the head out, Mr. Finlayson’ and in the head went. … The grog ran down the gutter in a stream. The men rushed out [and] threw themselves on the ground to drink it as it ran or collected in holes — some on their knees scooped it up with hands; others lay down and sipped it from the earth.” (10) Good grief.

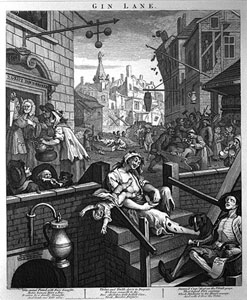

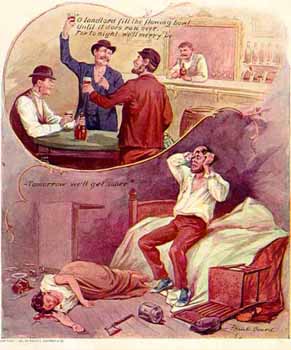

William Hogarth, Gin Lane, 1751. In England prior to the 1751 Gin Act, almost anyone could legally distill the stuff — and did. From 1730-50, men, women and children were notoriously and perpetually drunk. Note that in this dissolute landscape, the only robust structures belong to the pawnbroker, distiller, and funeral home. They’re playing a tune in McGuffy’s saloon, and it’s cheery and bright in there (God! but I’m weak — since the bitter dawn, and never a bite of food); I’ll just go over and slip inside — I mustn’t give way to despair — Perhaps I can bum a little booze if the boys are feeling good. They’ll jeer at me, and they’ll sneer at me, and they’ll call me a whiskey soak; (“Have a drink? Well, thankee kindly, sir, I don’t mind if I do.”) A drivelling, dirty gin-joint fiend, the butt of the bar-room joke; Sunk and sodden and hopeless — “Another? Well here’s to you!” Robert Service New Year’s Eve Situated near present-day Lethbridge at the forks of the St. Mary and Oldman Rivers, Alberta’s Fort Whoop-Up was indisputably the worst of a despicable lot. Though it’s sure to break politically correct hearts, the 200-mile chain of log stores, saloons, bordellos and misery known as the “whiskey forts”, was a wholly American venture. Established as HBC influence waned in 1869, Whoop-Up was a key factor in the 1873 formation of the North West Mounted Police (NWMP). Like a telegram from hell, a surviving letter neatly conveys the sordid ambience: “Dear Friend: My partner Will Geary got to putting on airs and I shot him and he is dead – the potatoes are looking well. Yours truly, Snookum Jim.”

The operative business ethic was equally distingue: Indians had hides for sale, and the traders had guns and whiskey – or something like whiskey. “Whoop-Up Wallop” consisted of a quart of whiskey, a pound of chewing tobacco, a handful of red pepper, a bottle of Jamaica ginger, and a quart of molasses. Predictably, the Indians were encouraged to imbibe before a price had been agreed on.  At Whoop-Up, “‘the trader stood at the wicket, a tub full of booze beside him,’ Colonel Sam Steele of the Mounties later recalled. ‘And when an Indian pushed a buffalo robe through the hole, the trader handed out a tin cup full of some poisonous concoction. A quart of the stuff bought a fine pony. When spring came, wagon loads of the proceeds of the traffic were exported to Fort Benton, south of the border.'” (11) As well, the region had attracted American “Wolfers”. They reckoned the easiest way to “catch” wolves was to lace buffalo carcasses with strychnine. But when native-owned dogs were poisoned, the natives attacked wolfers with guns obtained from the whiskey traders. Pouring gallons of rotgut whiskey onto this already volatile mixture, at a time when the government was desperately advertising for homesteaders, made policing an urgent priority. ..

At Whoop-Up, “‘the trader stood at the wicket, a tub full of booze beside him,’ Colonel Sam Steele of the Mounties later recalled. ‘And when an Indian pushed a buffalo robe through the hole, the trader handed out a tin cup full of some poisonous concoction. A quart of the stuff bought a fine pony. When spring came, wagon loads of the proceeds of the traffic were exported to Fort Benton, south of the border.'” (11) As well, the region had attracted American “Wolfers”. They reckoned the easiest way to “catch” wolves was to lace buffalo carcasses with strychnine. But when native-owned dogs were poisoned, the natives attacked wolfers with guns obtained from the whiskey traders. Pouring gallons of rotgut whiskey onto this already volatile mixture, at a time when the government was desperately advertising for homesteaders, made policing an urgent priority. ..

Bull Train, John Innes |  Shooting Up the Town, John Innes Charged with stamping out the whiskey trade, the appearance of the NWMP naturally provoked a lather of resentment among the traders, but, in the best tradition of the mortally offended, nearly all of them stayed. Perhaps they felt close quarters afforded a better vantage from which to criticize. One of the most bellicose was Harry “Kamoose” (the name means Squaw Thief) Taylor. When a shady and complicated deal went wrong, he was forever after convinced that all NWMP buffalo coats were stolen property that rightfully belonged to him – and said so – often. A graduate of Fort Whoop-Up, Harry moved on to preside over a Fort Macleod hotel. Outside that worthy establishment, a daunting sign featured a revolver pointing at a skull, and beneath, the lettering: “No Jawbone” (in modern parlance, No Credit) The house rules posted within, were pure, unadulterated Whoop-Up:

Shooting Up the Town, John Innes Charged with stamping out the whiskey trade, the appearance of the NWMP naturally provoked a lather of resentment among the traders, but, in the best tradition of the mortally offended, nearly all of them stayed. Perhaps they felt close quarters afforded a better vantage from which to criticize. One of the most bellicose was Harry “Kamoose” (the name means Squaw Thief) Taylor. When a shady and complicated deal went wrong, he was forever after convinced that all NWMP buffalo coats were stolen property that rightfully belonged to him – and said so – often. A graduate of Fort Whoop-Up, Harry moved on to preside over a Fort Macleod hotel. Outside that worthy establishment, a daunting sign featured a revolver pointing at a skull, and beneath, the lettering: “No Jawbone” (in modern parlance, No Credit) The house rules posted within, were pure, unadulterated Whoop-Up:  Enjoying Winter Patrol in One of Harry’s Coats Guests are forbidden to strike matches or spit on the ceiling, or to sleep in bed with their spiked boots and spurs on. Meals served in rooms will not be guaranteed in any way. Our waiters are hungry and not above temptation. To attract attention of waiters or bell boys, shoot a hole through the door panel. Two shots for ice water, three for a deck of cards, and so on. No tips must be given to any waiters. Leave them with the proprietor, and he will distribute them if it’s considered necessary. All guests are requested to rise at 6 a.m. This is imperative as the sheets are needed for tablecloths. Dogs are not allowed in the bunks, but may sleep underneathe. Insect powder for sale at the bar.

Enjoying Winter Patrol in One of Harry’s Coats Guests are forbidden to strike matches or spit on the ceiling, or to sleep in bed with their spiked boots and spurs on. Meals served in rooms will not be guaranteed in any way. Our waiters are hungry and not above temptation. To attract attention of waiters or bell boys, shoot a hole through the door panel. Two shots for ice water, three for a deck of cards, and so on. No tips must be given to any waiters. Leave them with the proprietor, and he will distribute them if it’s considered necessary. All guests are requested to rise at 6 a.m. This is imperative as the sheets are needed for tablecloths. Dogs are not allowed in the bunks, but may sleep underneathe. Insect powder for sale at the bar.

Crap, Chuck-luck, Stud Horse Poker and Black Jack games are run by the management. Indians charged double rates. Special rates to Gospel Grinders and the Gambling Perfesh. [sic] The bar in the annex will be open day and night. All day drinks 50 cents each; night drinks, $1.00 each. Only regularly registered guests will be allowed the special privilege of sleeping on the bar-room floor. A deposit must be made before towels, soap or candles can be carried to rooms. When boarders are leaving, a rebate will be made on all candles, or parts of candles, not burned or eaten. No kicking regarding the quality or quantity of meals allowed. Those who do not like the provender will get out, or be put out. Assaults on the cook are strictly prohibited.

Quarrelsome persons, also those who shoot off without provocation guns or other explosive weapons, and all boarders who get killed, will not be allowed to remain in the house. When guests find themselves, or their baggage, thrown over the fence, they may consider that they have received notice to quit. (11)

Harry wasn’t alone in his suspicions. There were dark mutterings that the NWMP were keeping all the whiskey for themselves. As Kipling was noticing about British troops in India, ‘single men in barracks don’t grow into plaster saints’. Sergeant S. J. Clarke of the Northwest, kept a journal from 1876 to 1884, at Fort Macleod and Fort Calgary: “His was a chronicle of non-stop poker games, fist fights, seductions, desertions, and gang drunks lasting for days. On New Year’s Eve, 1880, Clarke recorded that there were four hundred at the barracks ball and there was lots of drinkable Jamaica ginger. On January 2 more whiskey arrived and Clarke noted on January 3 the ‘C’ and ‘E’ Troops were both still drunk. … Some months later, Clarke reported another barracks party at which Corporal Patterson got into a drunken wrestling match with a squaw in the shoe shop. They knocked over the stove, which set fire to the shoe shop, the harness shop, and the big stable in which all the Mountie’s horses were kept. … In their carousing, brawling, and boozing the pioneer Mounties were only imitating the lifestyle that had long prevailed in the Red River Settlement and which was spreading westward wherever a new community was established.” (12) Questions were frequently raised in Parliament. Now sober as a judge, Sir John A. responded: “As regards the habits of the men, I think, on the whole, they are in a very fair state, but there is still a good deal of drinking. As the hon. gentleman knows, some of the force is stationed on the frontier, and there has been, I am afraid, a laxity in granting [liquor] permits. Besides … I have reason to believe also that there has been a great use of that most noxious alcoholic drink, Perry Davis’ Pain Killer. It contains a great quantity of alcohol, and has not only affected the physical health of the men, but the mental health of some of them. That has been used largely under the pretence of being medicinal, but, really, I am afraid, as a stimulant.” (13) …

Harry wasn’t alone in his suspicions. There were dark mutterings that the NWMP were keeping all the whiskey for themselves. As Kipling was noticing about British troops in India, ‘single men in barracks don’t grow into plaster saints’. Sergeant S. J. Clarke of the Northwest, kept a journal from 1876 to 1884, at Fort Macleod and Fort Calgary: “His was a chronicle of non-stop poker games, fist fights, seductions, desertions, and gang drunks lasting for days. On New Year’s Eve, 1880, Clarke recorded that there were four hundred at the barracks ball and there was lots of drinkable Jamaica ginger. On January 2 more whiskey arrived and Clarke noted on January 3 the ‘C’ and ‘E’ Troops were both still drunk. … Some months later, Clarke reported another barracks party at which Corporal Patterson got into a drunken wrestling match with a squaw in the shoe shop. They knocked over the stove, which set fire to the shoe shop, the harness shop, and the big stable in which all the Mountie’s horses were kept. … In their carousing, brawling, and boozing the pioneer Mounties were only imitating the lifestyle that had long prevailed in the Red River Settlement and which was spreading westward wherever a new community was established.” (12) Questions were frequently raised in Parliament. Now sober as a judge, Sir John A. responded: “As regards the habits of the men, I think, on the whole, they are in a very fair state, but there is still a good deal of drinking. As the hon. gentleman knows, some of the force is stationed on the frontier, and there has been, I am afraid, a laxity in granting [liquor] permits. Besides … I have reason to believe also that there has been a great use of that most noxious alcoholic drink, Perry Davis’ Pain Killer. It contains a great quantity of alcohol, and has not only affected the physical health of the men, but the mental health of some of them. That has been used largely under the pretence of being medicinal, but, really, I am afraid, as a stimulant.” (13) …

Cowpuncher, John Innes | N.W.M.P., John Innes In his Forty Years in Canada, Colonel Sam Steele made no secret of his own feelings about the force’s uncompromising (albeit hypocritical) mandate: “We had the detestable, prohibitory law to enforce, an insult to free people. Our powers were so great, in fact so outrageous, that no self-respecting member of the corps, unless directly ordered, cared to exert them to full entent. We were expected, on the slightest grounds of suspicion, to enter any habitation without a warrant, at any hour of the day or night, and search for intoxicants; no privacy was respected. Yet, owing to the pressure of a lot of fanatics who neither knew nor cared to understand the situation, parliament would not repeal the law and let the white people speak for themselves. This state of affairs continued for some years.” Until the early 1900s to be exact — by which time the public was voting for prohibition.”

Although man is already ninety per cent water, the Prohibitionists are not yet satisfied.

- ” – John Kendrick Bangs

“All his life the kid has been hearing of the evils of the drink, and how his loving mother suffered at the hands of his rotten father because of it. And, at the end of the threnody, ‘Ah, but it’s in the blood, I guess.’ [And when the boy does get drunk] the wrath of God descends. The priest comes into the house. He makes it clear that what you have done is worse than the violation of a vestal virgin. The mother of the house sobs quietly. The old man, craven, orders another beer at the corner saloon.. … If a system has been devised to produce a confirmed alcoholic to exceed this one in efficiency, I know it not.” (14)

It’s probably futile to speculate what has damaged more brain cells, caused more automobile accidents, domestic violence, ulcers, grief, and deaths: long years of bad social policies devised by liberal ninnies, or cigarettes, liquor, and other legal commodities consumed by a harried public frantically seeking just one single moment’s respite from the interminable bullying, nagging, and hectoring. In the normal course of things, “temperance” means moderation, a balanced and self-disciplined way of dealing with one’s appetites; but for more than a century now (in the way of all politicized words) “temperance” has meant an absolute and total ban. When alcoholic beverages (cigarettes, guns, and other sundry evils) are not banned outright, the government thoughtfully imposes extravagent taxation to assuage our collective consciences.

- “How well I remember my first encounter with The Devil’s Brew. I happened to stumble across a case of bourbon — and went right on stumbling for several days thereafter.” W. C. Fields, The Temperance Lecture

As the affable, bumbling drunk has vanished from our entertainments, the professional alarmist and cultural interpretor has assumed centre stage. No one now worries on his own behalf. No one says: “Advertising made me smoke against my better judgement! I couldn’t stop myself. When I saw those magazine advertisements, I just had to drink my first forty-pounder!” No. It’s a compelling humanitarian concern for what other — susceptible — people are likely to do. The proof is that, so far, other people are free to make decisions we don’t always like. So what?

When they came for the smokers I didn’t speak up because I don’t smoke. When they came for the drinkers I didn’t speak up because I’m a teetotaller. When they came for the meat-eaters I didn’t speak up because I’m a vegetarian. When they came for the motorists I didn’t speak up because I’m a cyclist. They never did come for me because there’s nobody left but sissies with rickets.

LINKS

Modern Drunkard Magazine – where PC means Pimm’s Cup

Superb! Perfect Your Drinking Technique – Troubleshooting & Remedial Action The Darwin Awards – honouring those who have laid down their lives in the service of stupidity * See if you can identify which hare-brained schemes were alcohol-fueled * Don’t miss 1982 “honourable” mention – “Balloon Chair Larry” It Tastes Light! – Miller responds to “free beer” hoax “Alcohol and Minorities” – Ethnic drinking patterns – National Institutes of Health (US) Smoking & Drinking – Hyperbole & Propaganda – an excellent defense of sanity and humour Why prohibiting attitudes and behaviours is an expensive route to a lost cause On the other hand – Kill a Brain Cell, Go to College REFERENCES: (1) Rorabaugh, W.J., The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition, Oxford University Press, New York, 1979, p26. (2) Samuel de Champlain, The Voyages, 1613 (3) Levine, H.G., “The Good Creature of God and the Demon Rum,” pp. 111-161 in National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Research Monograph No. 12: Alcohol and Disinhibition: Nature and Meaning of the Link, NIAAA, Rockville, MD, 1983, p. 115. (4) Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic, p30. (5) Talbot, Edward Allen, Five Years Residence in the Canadas: including a Tour Through Part of The United States of America in the Year 1823 London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green, 1824 (6) Rowan, John J., The Emigrant and Sportsman in Canada. Some Experiences of An Old Country Settler. With Sketches of Canadian Life, Sporting Adventures, and Observations on the Forests and Fauna London: Edward Stanford, 1876 (7) W.J. Eccles, The Canadian Frontier 1534-1760, pp 97-8 University of New Mexico Press, 1976 (8) Leslie Hannon, Redcoats and Loyalists, 1760 / 1815, p 41, Canada’s Illustrated Heritage, 1978 (9) Robert Melrose, 1853, B.C. Archives E/B/M49.1/page 18, page 24 (10) John Helmcken’s Reminiscences, B.C. Archives, AddMss 505/volume 12/page 23 (11) Frank Rasky, The Taming of the Canadian West, pp 178,182, McClelland and Stewart 1967 (12) James H. Gray, Red Lights on the Prairies, Western Producer Prairie Books, 1986 pp 3-5 (13) Sir John A. Macdonald, Debates, House of Commons, 1881, pp 1,327 (14) McCabe, C., The Good Man’s Weakness, Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1974, pp. 31-32.